*This research was supported by the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa “Library Treasures Award” (Summer 2022)

Since the early twentieth century, “miscegenation” in Hawaiʻi has received a relatively large amount of attention from U.S. scholars. This is perhaps not surprising, given that the state of Hawaiʻi was, and is still today, home to the nation’s largest share of mixed-race Americans.[1] In the U.S. imaginary, Hawaiʻi has been conceived as some sort of fictive racial utopia or “melting pot”, with some people even going so far as to suggest that the archipelago hosts a “post-racial” society.[2] This erroneous image of racial egalitarianism in Hawaiʻi can be traced back to an influential body of literature produced in the early twentieth century by haole (white, not Native Hawaiian) anthropologists and sociologists who perceived the Hawaiian Islands, in the words of Leslie C. Dunn, as “a great natural experiment in racial hybridization”.[3]

These studies conducted by haole social scientists on the topic of interracial sex and its consequences in Hawaiʻi have been well-documented from a history of science perspective. The numerous and varied hypotheses on miscegenation in Hawaiʻi that were produced in the 1920s and 1930s have been critiqued by historians such as Warwick Anderson, Christine Manganaro, and Maile Arvin.[4] But a U.S.-centric narrative examining the impact that white men’s ideas about multiracialism in Hawai‘i had in the U.S. continent tells us remarkably little about the history of mixed-race experiences in Hawaiʻi. Although anthropologists and social scientists have used oral histories to investigate contemporary interracial experiences and mixed-race identity formations, a locally grounded historical study concerning the lives, experiences, and identities of interracial couples and their mixed-race children is yet to be written about Hawaiʻi.[5] With that said, it must be noted that both Arvin and Manganaro have made efforts to include mixed-race Native Hawaiian voices within their respective studies of the history of haole science.[6] Brandon C. Ledward’s anthropological investigation into the meaning of hapa identity also includes some historical perspective.[7] David Chang, moreover, seamlessly integrates histories of interracial mixture of the Kānaka Maoli diaspora – an otherwise understudied topic – into his analysis of Native Hawaiian geography and exploration.[8]

Reorienting away from a history of knowledge production about multiracialism in Hawaiʻi, this article provides a glimpse of what mixed-race history in early to mid-twentieth century Hawaiʻi looks like “from below”. Taking a critical approach to mixed-race studies as a Western-centered discipline, what follows is a discussion of the colonial violence that has been enacted through the “Part Hawaiian” category, as well as an exploration of the diversity of interracial dating experiences on the islands along ethnic and gendered lines. Rather than adding to discussions about how multiracialism in Hawaiʻi was understood on the U.S. continent, I use archival materials to re-center the self-identities and lived experiences of those people who appear in the published historical record only as i) statistics for “out marriage” and ii) the “hybrid” subjects of anthropometric investigation. Scientifically speaking, there is of course no such thing as “mixed-race”. Race is not a fixed biological category, but a socially constructed way of classifying people according to their phenotypical features and ancestry.[9]

Whose “racial laboratory”?

Currently, the literature on miscegenation in Hawaiʻi tells the tale of early twentieth century American eugenicists and social scientists who treated Hawaiʻi as a “racial laboratory” for the United States of America. In response to the perceived threat that “human hybrids” posed to the white civilisation of the United States, Hawaiʻi attracted unique interest among haole scholars in the 1920s and 1930s as a “crossroads” where “all the races of the Pacific meet and mingle on more liberal terms than they do elsewhere”.[10] With its unique demographic and relatively high rate of interracial marriage, white American intellectuals found in Hawaiʻi the opportunity to observe, for the very first time, the outcome of free intermixture between “Caucasians”, “Asians”, and “Hawaiians”. In his study of the “Oriental Problem” in the U.S.A., historian Henry Yu concludes that Chicago School sociologists perceived Hawaiʻi as their “fantasy island […] the ultimate racial laboratory, a place where the formation of the cultural melting pot they had predicted for the West Coast was already taking place”.[11] From its inception, academic interest in interracial mingling in Hawaiʻi was guided by discussions about miscegenation and its effects on the U.S. continent.

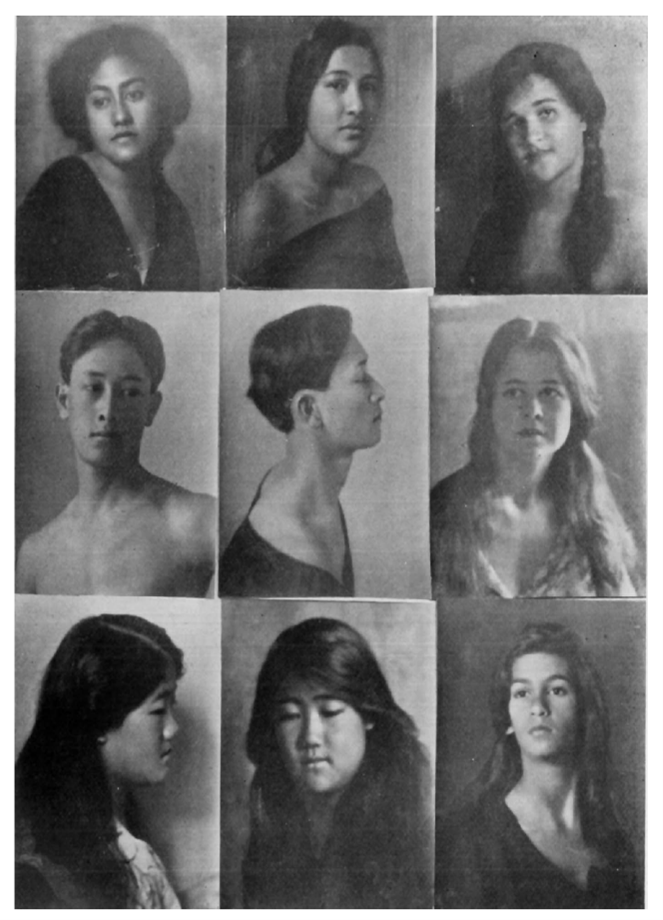

The fifty portrait photographs of “Hawaii’s mixed-race children” that were taken by haole photographer Caroline Gurrey in the period 1905-1909, for instance, generated greater interest among eugenicists in continental U.S.A. than they ever did in Hawaiʻi.[12] Whilst Gurrey’s personal intention was to use the art of photography to “preserve in pictures the particular racial combinations that she believed would disappear”, anthropologist Alfred M. Tozzer sponsored the display of her photographs at the Second International Congress of Eugenics (Figure 1) which was held at the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) in 1921. There, they found new meaning in eugenic circles as part of an exhibit titled “Hawaiian Hybrids”, with it being suggested that they could be used to predict what would happen if other racial groups were allowed to mix with white Americans.[13]

As Anderson has illustrated, AMNH staff thereafter grew eager to gain authority over “the entire Polynesian field so that in the future [the] Museum [would] be looked to as a center for this subject”.[14] Continental interest in the “mixed-race question” not only emanated from the West Coast, therefore. Echoing the sentiments of the Chicago School, the AMNH’s President declared in a private letter in 1920 that the study of Hawaiʻi would shed light on racial intermixture in New York and other parts of the mainland.[15] Evidently, it was white Americans on the West and East sides of the continent who felt they had most at stake in Hawai’i’s “great experiment in race mixture”.[16] What this narrative tells us is that U.S. scholars were not conducting research for the sake of benefitting Hawaiʻi and its people. In 1931, University of Hawaiʻi sociologist Romanzo Adams, who had himself been trained at the University of Chicago, explicitly reminded his benefactors at the Rockefeller Foundation in New York that “The study of race relations in Hawaii is not primarily for local purposes. It is intended to throw light on a world situation”.[17]

Stemming from anxieties about the amalgamation of Black and white communities in the United States of America, the term “miscegenation” was coined in 1864 to denote what white people perceived as the undesirable phenomenon of the “interbreeding of races”.[18] More than anything, anti-miscegenation laws on the continent reflected deep-rooted fears about white women having children with African American men, with W.E.B. Du Bois describing the miscegenation threat – or the “Black peril” – as “the crux of the so-called Negro problem in the United States”.[19] Following the influx of Asian immigrants into the United States in the late nineteenth century, however, the national “miscegenation question” expanded its scope to include the perceived racial threat posed by Chinese and Japanese Americans.[20] Accordingly, the white population grew evermore anxious about the threat of so-called “mongrelisation” – the dilution of the white race through hybridity. Advocates of the racial sciences were forced to redefine “whiteness” as they struggled to categorise, within their established racial hierarchies, the generations of mixed-race individuals who began to appear in greater and greater numbers and with increasingly diverse phenotypical features.

As in Europe, debates about the desirability of miscegenation in the U.S.A. were fuelled by the spectre of racial degeneration, the eugenics theory that certain non-white ethnic groups and lower social classes, such as sex workers, criminals, and the poor were, by their heredity, morally defect and thus representative of a regression in human evolution.[21] By 1916, American lawyer and eugenicist Madison Grant had predicted the extinction of the white American race, stating that the act of “[bringing] half breeds into the world” was “a social and racial crime of first magnitude”.[22] In eugenic thinking, interbreeding between morally defective groups should be highly regulated for the greater good of (white) civilisation.[23] As a measure to protect the “purity” of the white American race, some states, beginning with Tennessee in 1910, introduced the “one drop rule”. In the Racial Integrity Act of 1924, for example, Virginia strictly defined a “white person” as one “who has no trace whatsoever of any blood other than Caucasian, or has one-sixteenth or less American Indian blood and no other non-Caucasian blood”.[24] Responding to the growth in America’s mixed-race population coupled with the emergence of local “mulatto” culture in parts of the country such as Harlem, New York, leading Harvard University anthropologist Earnest A. Hooton stated in 1926 that “miscegenation is perhaps the most important field of research in anthropology today”.[25]

It was within this context of increased interest in the consequences of racial intermixture that the newly annexed territory of Hawaiʻi came to be conceived in the wider U.S. imagination as “a centre of miscegenation”, a research site where anthropologists and geneticists would find “a tempting opportunity […] to study the inheritance of racial traits”.[26] White American attitudes were generally more liberal towards interracial sex taking place in the offshore territory of Hawaiʻi, where there were never any anti-miscegenation laws, than they were when it came to the prospect of interracial marriages taking place on the continent.[27] It came to be believed that “a new type of man was being developed” in Hawaiʻi and many haole observers championed marriage between particular racial groups on the islands – with unions between Native Hawaiian women and Chinese men being the most favoured.[28] As early as 1917, American statistician Frederick L. Hoffman remarked that “the intermixture of native women with full-blood Chinese has produced a physically and morally superior type”.[29] This sentiment was also echoed in 1920 by Henry Fairfield Osborn, the aforementioned President of the AMNH, who stated “the Hawaiian and Chinese blend is an excellent one; in the schools, intelligent, upright, persistent”. That same year, Charles J. McCarthy, the Territorial Governor of Hawaiʻi, concurred that they were “the next-best hybrid besides those of Hawaiian and European ancestry”.[30] Perhaps the most influential haole scholar on the subject of interracial marriage and “assimilation”, however, was Romanzo Adams, who became the University of Hawaiʻi at Manoa’s first Professor of Sociology and Economics in 1920. Adams argued that the islands’ history was characterised by remarkably amicable racial intermixing that would eventually result in the birth of a “Neo-Hawaiian American race”, otherwise dubbed the “Golden Man”.[31]

What we see from a history of science perspective is that Hawaiʻi’s diverse demographic captured the intellectual imagination of a new generation of white American male scholars who perceived racial intermixture as a social and cultural issue, rather than a strictly biological one. As Anderson has illustrated, this social scientific research that praised racial intermixture in Hawaiʻi in the 1920s and 1930s played a central role in an intellectual shift in the U.S.A. away from the biological racial sciences of the nineteenth century.[32] Challenging Anderson’s conclusions, however, Arvin has reminded us that we should acknowledge this transition away from scholarly condemnation of intermarriage without falling into the trap of celebrating it as a “liberal moment” for the social sciences.[33] After all, as discussed in the following section, many of these studies continued to perpetuate harmful racial typologies and biological hierarchies, whilst subscribing, at least partially, to the doctrines of eugenics.

Violence against indigeneity and the “Part Hawaiian” typology

The discipline of mixed-race studies must remain self-reflexive in its approach, beginning with a criticism of the very term “mixed-race”. In the early twentieth century American imagination, multiracial people were believed to occupy an intermediary position somewhere between the races of their parents. In 1931, American sociologist Robert E. Park summarised the prevailing view of his day: “The most obvious and generally accepted explanation of the superiority of mixed bloods is that the former are the products of two races one of which is biologically inferior and the other biologically superior”.[34] Nevertheless, the concepts of racial “purity” and “hybridity” are entirely fictional. There is of course no scientific basis for any such thing as a discrete genetically homogenous race of human beings. “Race” is a socially constructed, Western way of classifying people with similar phenotypical features and common ancestry, and we must be careful not to reproduce an essentialist mode of thinking.[35] The notion of grouping multiracial people into a single unified category has always been absurd, especially within the logic of “race science” in which the concept has its origins. Multiracial people are not homogenous, and they do not necessarily share physical features, heritage, or culture with one another.[36]

In response to the “mixed-race problem” in Hawaiʻi, anthropologists and sociologists constructed a dominant racial typology – namely the “Part Hawaiian” typology – through which they believed they could classify and study the outcomes of the most biologically significant varieties of racial intermixture. It is well-documented that interracial sex had been taking place between white men and Native Hawaiian women since the arrival of British Captain James Cook on the islands in 1778.[37] According to Romanzo Adams’ influential 1937 publication Interracial Marriage in Hawaii, by 1848 there were three times as many European whalers and fur traders with Native Hawaiian wives than with European wives. The children born from these early relationships were described as “half caste” if they were deemed legitimate, meaning they were born within the institution of marriage; or “Hawaiian” if they were deemed illegitimate, meaning they were conceived from the casual sexual liaisons of white sailors on the islands and subsequently raised by their Native Hawaiian mothers.[38]

Seemingly, it was not until the 1900 United States Census that the “Part Hawaiian” typology was introduced.[39] As evidenced in the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi censuses for 1866, 1878, and 1890, the term “half-caste” and its Hawaiian translation “hapa haole” were used to classify mixed-race people in the nineteenth century.[40] Given the small number of foreign women on the islands, the vast majority of those individuals who were listed as “half-castes” had a Native Hawaiian mother. The immigration of many single Chinese, Japanese, and Filipino male plantation labourers into Hawaiʻi after the 1850s, moreover, led to increased intermarriage between Native Hawaiian women and foreign men.[41] Marriage records from 1853 show that 72.6% of foreign men who had married in Hawaiʻi had wed Native Hawaiian women.[42] The existing data tells us that the number of mixed-race Native Hawaiians continued to increase in the second half of the nineteenth century, despite the overall number of Native Hawaiians declining between 1850 and 1896 (Figure 2). It is worth drawing attention to the fact that interracial relationships in Hawai’i were explicitly gendered from the very beginning. In an anthropometric study published by the Peabody Museum in 1928, only 1 of the 37 “Caucasian Hawaiian” subjects had a haole mother and Native Hawaiian father. As Leslie C. Dunn commented, this reflected contemporary marriage statistics which showed at the time “that most persons of mixed blood in Hawaii originate in matings of Hawaiian women and men of other races”.[43] Nearly all interracial marriages in Hawai’i that occurred before 1950 involved Native Hawaiian, Asian, or multiracial women.[44]

| Year | Recorded number of mixed-race Native Hawaiians in Hawaiʻi |

| 1853 | 983 |

| 1860 | 1,337 |

| 1866 | 1,640 |

| 1872 | 2,468 |

| 1878 | 3,420 |

| 1884 | 4,218 |

| 1890 | 6,186 |

| 1896 | 8,485 |

| 1900 | 7,857 |

| 1910 | 12,506 |

| 1920 | 18,027 |

| 1930 | 28,224 |

| 1940 | 49,935 |

| 1950 | 73,885 |

The 1900 U.S. Census, which was the first U.S. Census to include Hawaiʻi, recorded 7,857 “Part Hawaiians” across the islands.[45] In the 1910 Census, this number increased to 12,506, and two new sub-categories were introduced. The first was “Caucasian Hawaiian”, to which 8,772 “Part Hawaiians” were designated. The other 3,784 individuals were assigned to the category of “Asiatic Hawaiian”, a term which was later used interchangeably with “Chinese Hawaiian” or “hapa pake”.[46] These arbitrary classifications were highly influential in sociological and scientific circles, forming the basis of analysis for the research conducted by Louis Robert Sullivan, Romanzo Adams, and others. In Hawaiʻi, “Caucasian Hawaiian” and “Chinese Hawaiian” were the only multiracial classifications to appear in the 1920 and 1930 censuses.[47] Nevertheless, in 1940 they were dropped from the “color and race” column in favour of a return to the more generic “Part Hawaiian” classification (shorthand “PHa”).[48] In 1950, individuals could only be assigned to a monoracial category, although the Yes/No question “is this person of mixed race?” was also required.[49] This meant that a person could be identified as both “Hawaiian” and “of mixed race”. It was not possible to identify with two or more races in the U.S. Census until 2000, however, meaning that historic census data on mixed-race people is rather ambiguous.[50] Testament to the lack of consistency toward the categorisation of mixed-race Native Hawaiians in U.S. thought, the “Part Hawaiian” category was once again re-introduced, making its final appearance in the census of 1960.[51]

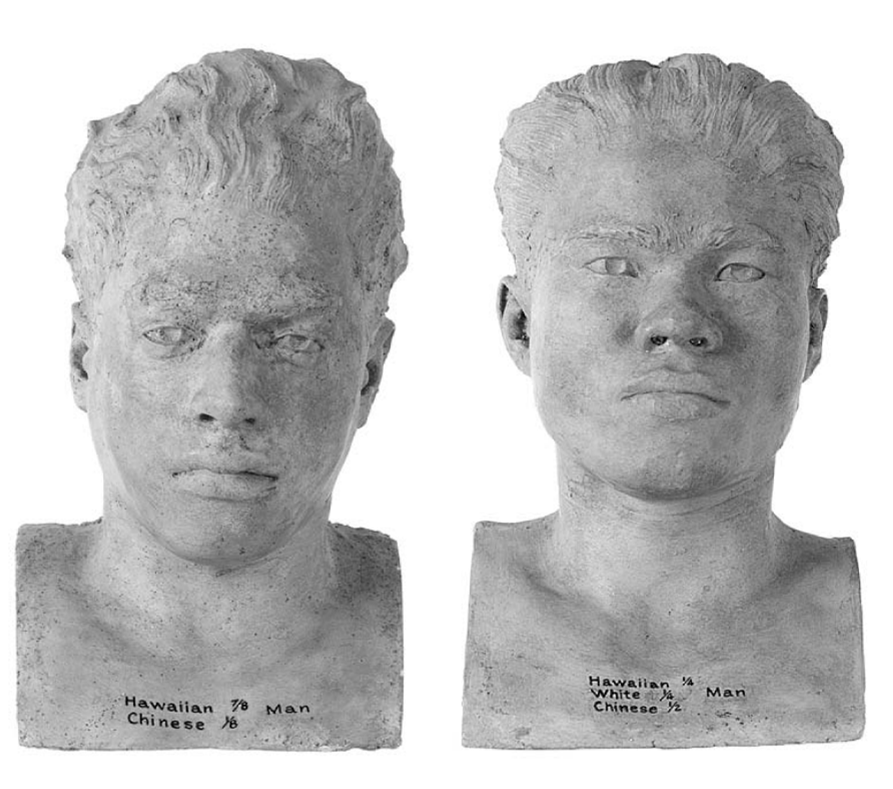

Speaking at the Eugenics Congress in New York in 1921 where his work was displayed alongside Caroline Gurrey’s photographs, haole physical anthropologist Louis R. Sullivan stated that “the Part Hawaiian is biologically a better individual than the full Hawaiian – more capable of coping with modern conditions of life and civilization”.[52] Funded by the AMNH, Sullivan worked in collaboration with the Bishop Museum in Honolulu in the period 1920 to 1925 to create an extensive collection of 11,000 physical measurements, 1,300 photographs, and numerous plaster casts documenting the Native Hawaiian people and their new “hybrid mixes” (Figure 3). Being sponsored to investigate the characteristics of the fictional “Pure Hawaiian” race, Sullivan’s research methods were highly intrusive.[53] He took blood and hair samples from kamaʻāina (residents of Hawaiʻi), measured the crania held in the Bishop Museum’s collections, and measured skulls that Bishop Museum staff had exhumed from Native Hawaiian burial sites.[54] Moreover, his funders in New York insisted that he photographed Native Hawaiians naked so that the images would attract more interest at eugenics exhibitions.[55] Many of his live subjects were mixed-race Native Hawaiian students at Kamehameha Boy’s school, which conveniently shared its grounds with the Bishop Museum.[56]

Building on his belief that “Part Hawaiians” benefitted from a kind of “hybrid vigor” that granted them a biological advantage over “Pure Hawaiians”, Sullivan concurred with earlier thinkers like Hoffman and Osborne that “Chinese Hawaiians” were the group best adjusted to modern life.[57] Although Sullivan might appear to have been an early champion for mixed-race Native Hawaiians, his attitude towards miscegenation was far from progressive. Rooting his work in eugenic ideas of “degeneration”, Sullivan firmly upheld the theory of white supremacy and subscribed to the belief that Asians occupied an intermediary position between “superior” whites and “inferior” Native Hawaiians, all within a strict racial hierarchy. By suggesting that “Part Hawaiians” were a “step up” from their Native Hawaiian parent on the racial ladder, Sullivan insisted that they should be classified as a “step down” from their Chinese or haole parent.[58] In correspondence with Charles Davenport regarding the subject of mixed-race Native Hawaiians, Sullivan remarked that “from the standpoint of whites or Chinese, [racial hybridity] is a failure of course”.[59] This theory remained popular among haole scholars for several decades, being echoed by Adams in 1937, for example, who remarked that “In school, the Chinese-Hawaiians are retarded more than the Chinese, less than the Hawaiians”.[60]

It is worth noting here that when Sullivan suddenly died in 1925, the AMNH and Bishop Museum replaced him with Harry Shapiro, another young anthropologist and eugenicist who would continue to collect measurements from mixed-race Polynesians. For his project in Hawaiʻi, Shapiro hired William A. Lessa as his student assistant. Lessa was responsible for conducting fieldwork on “Chinese Hawaiian crosses”.[61] After collecting measurements on more than one thousand individuals in Hawaiʻi, Lessa concluded that most “Chinese Hawaiians” in fact had “Haole blood”.[62] Lessa’s disappointment that his subjects were not exclusively of Chinese and Native Hawaiian ancestry is echoed in a series of 202 interviews that Margaret Lam conducted with “Pure Chinese Hawaiians” in the period 1930 to 1931. Lam, a Chinese American student of Romanzo Adams at the University of Hawaiʻi, marked on some of the interview papers that they were “thrown out” in light of the discovery that the individual had Japanese or haole great grandparents.[63] Despite the oxymoron, social scientists came to be preoccupied with the search for the “pure hybrid”. In this mode of thought, it was tri-racialism which threatened the integrity of the supposedly superior bi-racial “Chinese Hawaiian” mix.

Through enforcing the “Part Hawaiian” category and its variants, scholars and administrators actively disregarded the way that Native Hawaiian people chose to self-identify. Writing about Sullivan, Arvin notes that he “often doubted and disregarded the self-identifications his Native Hawaiian subjects made, marking many of those who claimed to be ‘Pure Hawaiian’ as ‘Part Hawaiian’”.[64] If we read between the lines of anthropological studies about Hawaiʻi rather than taking their claims at face value we can see that, much to the frustration of haole scholars, many Native Hawaiians resisted and challenged the “Part Hawaiian” typology. Within the scope of her research conducted under Romanzo Adams in the early 1930s, many of Lam’s “Chinese Hawaiian” interviewees, who were explicitly asked to give their opinion on i) “Chinese” ii) “Hawaiians” iii) “Chinese Hawaiians” and iv) “Caucasian Hawaiians”, stated that they regarded the latter two categories as simply “Hawaiian”.[65] What these interviews show is that those who were “hybrid” in the eyes of haole social scientists did not necessarily identify as such. Often, the interviewees invoked monoracial identity formations, self-identifying with only their “Chinese” or “Hawaiian” ancestry. Alfred Man, a 24-year-old in Honolulu, for instance, stated “I take myself as Hawaiian. I never think of the Chinese side”.[66] Likewise the interviewer’s note about Maui-born Perdita Jackson, who was raised by her Native Hawaiian aunt, reads: “Feels very much at home with [Hawaiians]. Proud she is Hawaiian and says she can ‘boost’ Hawaiian people any time […] Takes her Chinese-Hawaiian friends as Hawaiian. Never thinks of the Chinese side”.[67]

Furthermore, in 1930, Shapiro’s student assistant William A. Lessa lamented about the lack of “Pure Hawaiians” on the islands, writing to Shapiro that “Many of those who claim to be pure Hawaiians are quite apparently mixed”.[68] A month later, he continued to vent his frustration about what he saw as a deceitful “race”, stating that “They lie right to your face […] and it is only by roundabout ways that I do discover other mixtures. The less I say about the Hawaiians the better”.[69] Rather than portraying Native Hawaiians as a dishonest people, Adams himself blamed their perceived lack of knowledge. In 1937, he wrote that “Part Hawaiians, especially the darker complexioned ones, frequently are ignorant of their possession of non-Hawaiian blood or they think that their little non-Hawaiian blood is of no practical importance and so they claim to be full blood Hawaiians”.[70] Later, in 1955, sociologist Andrew W. Lind (who had been Adam’s colleague at the University of Hawaiʻi before his retirement in 1934) portrayed the mixed-race Native Hawaiian as a curious enigma for Western onlookers, stating that “One of the most striking of Hawaii’s many paradoxes is that one of the largest ethnic groups, stressing its unique heritage from one native source, is in fact the most racially mixed of all Hawaii’s peoples”.[71]

Ironically, what these accounts evidence is not Native Hawaiian ignorance, but the ignorance of haole scholars. To repudiate Lind, it might be said that one of the most striking paradoxes of haole social science in this period is the continued use of the “Pure” and “Part Hawaiian” binary, despite unanimous acknowledgement in scientific circles that there is no such thing as an “unmixed race”. Adams even begins his book by stating “It is no longer a secret, even to the layman, that there are not now and probably never have been […] any pure races”.[72] The very idea of being “part” indigenous violated Kānaka understandings of Native genealogy.[73] Native identity was not quantifiable. And it could not be “diluted”. In her book Hawaiian Blood: Colonialism and the Politics of Sovereignty and Indigeneity, J. Kēhaulani Kauanui explains that “Hawaiians’ traditional form of considering who belongs and who descends from the āina (land) relies on bilateral descent over and above constructions of blood quantum”.[74] The fractionalising discourse of “Part Hawaiian-ness”, which perpetuated the idea that indigeneity could be measured through blood, laid the foundations for an emerging discourse about the extinction of the Native Hawaiian “race”. Rather than seeing racial intermixture as a method of cultural resilience and a way of expanding the Native community, it has been interpreted as their dissolution, “a project of disappearance”.[75] In Arvin’s words, “Native Hawaiians have long been inclusive about their genealogical definitions of community and nation in a desire to grow their relations”.[76] Ever since the Blood Quantum legislation was introduced by the Hawaiian Homes Commission Act in 1921, however, mixed-race Native Hawaiians with “less than half” Kanaka blood have been branded “inauthentic” in the eyes of the law.[77] Highlighting the flawed logic behind the blood quantum construction, Kauanui points out how the idea of Native blood dilution contradicts popular understandings of the hyperdescent of African American heritage on the U.S. continent, where Black identity is “not premised on the exclusion of other racial identities”.[78]

Drawing on his own hapa haole experience, nonetheless, Brandon Ledward’s Ph.D. thesis challenges the simple, inclusive understanding of Native Hawaiian genealogy in which you either “are or are not Native Hawaiian”. As Ledward highlights, mixed-race experiences of belonging to the Kānaka community are “shifting and complex”, and many mixed-race Native Hawaiians have faced exclusion from the Native Hawaiian community based on their phenotypical appearance.[79] Ledward’s study of contemporary identity formations around the concept “hapa” reminds us that the “Part Hawaiian” typology has been internalised and reappropriated by Native Hawaiians, including mixed-race Native Hawaiians, over the past 100 years. As Ledward explains, the term “hapa”, when used by Native Hawaiians, is understood to indicate Native Hawaiian ancestry, although it is now more commonly used outside of Hawaiʻi by people with mixed Asian ancestry.[80] On the one hand, there is certainly a kind of violence in the way that the “Part Hawaiian” typology has led to the exclusion of some mixed-race individuals from claiming Native identity; and along with haole administrators, Native Hawaiians have played a part in the gate-keeping of indigeneity and the consequent ostracisation of mixed-race Native Hawaiians. On the other hand, however, reclaiming the hapa haole category has also enabled many individuals to simultaneously embrace both their Native Hawaiian and other heritages. In other words, “The concept of hapa allows a person to be at once Hawaiian and non-Hawaiian without experiencing internal divisions or a sense of loss”.[81] In most contemporary contexts, the term hapa has lost its original connotation of “half, not whole”, more often translating as “mixed”.

Essentially, Ledward prompts us not to underestimate the extent to which mixed-race Native Hawaiians have formulated and articulated their own identities depending on their personal circumstances. When we look back to the early twentieth century, we see that mixed-race Native Hawaiian identity was constantly being contested and reformulated. Whilst many did refute the “Part Hawaiian” typology, the historical evidence also suggests that some people detested and distanced themselves from their own Kānaka heritage, having internalised popular ideas about racial hatred toward Native people. In the early 1930s, Lam found that over half (55%) of her “Chinese Hawaiian” interviewees had negative or conflicting feelings about Native Hawaiians, reproducing negative stereotypes about them being lazy, gossiping, troublemaking, and vengeful.[82] Others among them socialised only with other “Chinese Hawaiians”, noting that the Chinese community refused to mingle with them on the grounds they were “Hawaiian”, even though they did not self-identify as such.

Certainly, there was no uniformity in the way that mixed-race Native Hawaiian individuals self-identified. The prevalence of uneasy feelings toward their own Kānaka ancestry is noteworthy, however. Maria Akana, a 24-year-old whose mother was Native Hawaiian and father was “Chinese Hawaiian”, was noted to have not liked Native Hawaiian people at all; when asked about her attitude toward other “Chinese Hawaiians” she said that she was “not at ease with them in general” because they were “inclined to be too much [Hawaiian] for her”.[83] 21-year-old Mrs. Ethel Kong, who specified that “Chinese Hawaiians” were her favourite group to be around, stated “I have no use for Hawaiians. Now when I think of them I feel disgusted”.[84] These kinds of anti-Native sentiments were echoed across many of the interviews, with other comments reading: “Hawaiian: Dislikes this group very much. Has gone as far as to not feel at home with own grandparents now”; “dislikes her Hawaiian relatives”; “Regrets that she has a quarter Hawaiian—dislikes this group very much”; and “Does not wish to identify herself with this group. Regrets she has Hawaiian blood”.[85] In a similar vein, an interview regarding a 13-year-old child noted: “Mother didn’t want children to mingle with Hawaiian people. Very seldom play with own cousins”.[86] In an earlier series of interviews that Lam conducted with “Chinese Hawaiian” couples, she found that most of them “emphasized their ‘Chinese blood’ and denied the influence of their ‘Hawaiian blood’”. As Manganaro summarises:

“Some of them said they thought Chinese blood was more robust than Hawaiian blood, that it had more of an effect of making them who they were than Hawaiian blood […] Quoting heavily from her interviews, Lam reported that many of her informants believed strongly in ‘the destructiveness of Hawaiian blood’ and that Chinese blood produced ambition, among other positive traits. ‘This racial myth,’ she said, ‘is a real thing to these hybrids,’ whom she says claimed biological superiority to Hawaiians”. [87]

What this series of unpublished interviews underscores is that mixed-race Native Hawaiians clearly negotiated their own identities, choosing on their own terms whether to discard or adopt the labels that haole social scientists created for them. Nevertheless, it must be added that the interview data is not unmediated and that Lam’s position as a Chinese American may have influenced the responses of some of her interviewees, who rarely spoke ill of the Chinese community. Moreover, mixed-race identity is seldom “fixed”. It can change over the course of a lifetime, and it can also change across different social spaces; this kind of code-switching is not unusual. Evidently, many did form collective identities based on the “Chinese Hawaiian” and “Caucasian Hawaiian” classifications. Given that there was widespread stigma towards Native Hawaiian people at this time, however, choosing to discard one’s own Native Hawaiian heritage often brought with it social benefits. The popular racialised views of the day clearly had a negative impact on the way that some mixed-race people viewed their own Native Hawaiian ancestry. Even today, the violence of the “Part Hawaiian” typology can be observed from the fact that it still functions to legitimise blood quantum logic, which is used to by haole settlers to dispossess Native Hawaiians of their lands as well as their Indigenous identity.[88]

Interracial dating experiences: what can we learn from the archives?

Contrary to the view of a “racial paradise” that was put forward by Romanzo Adams in his 1937 study on interracial marriage across the islands, unpublished papers held at the University of Hawaiʻi’s Archives provide evidence for the widespread existence of racial prejudice in Hawaiʻi. Along with Lam’s interviews with “Chinese Hawaiians”, there is a series of essays written by sociology students at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa in the 1940s-1960s held in the Romanzo Adams Social Research Laboratory (RASRL) collection. These essays contain a wealth of evidence about mixed-race and interracial dating experiences in early to mid-twentieth century Hawaiʻi, including personal attestations and original oral interviews. As discussed in the previous section, the mixed-race typology produced by haole social scientists was centered around “hybrids” with Native Hawaiian ancestry – the so-called “Part Hawaiian”. Except for the 1950 census (which technically allowed people from any “single race” to be identified as also being “of mixed-race”) there was no possible way for people of other mixed-race backgrounds to identify themselves in the official records from 1900 to 1960. What is valuable about this collection of anonymous student essays, therefore, is that they contain information about romantic interracial encounters in this period that do not necessarily involve Native Hawaiians.

Generally speaking, marriage trends ebbed and flowed in accordance with changing gender balances among different ethnic groups on the islands. In the nineteenth and early twentieth century, for example, “Part Hawaiian” men were most likely to marry Native Hawaiian women, whereas an estimated 50% of “Part Hawaiian” women married foreigners. This was reversed, however, when more foreign women arrived on the island.[89] Male immigrants increasingly married within their own communities, especially the Japanese. By 1947 only 3% of Japanese men were married to non-Japanese women.[90] In the period 1907-1923, approximately 14,276 picture brides traveled from Japan to Hawaiʻi.[91] Notably, some of these “brides” came to Hawaiʻi for sex work, with Joan Hori’s study of Japanese prostitution finding that Chinese men were their “best customers”.[92] Whereas sex work was policed, however, interracial marriage was legal and therefore seems to have been the preferred expression of interracial romance.[93] We can observe, furthermore, that the arrival of more Japanese, Filipino, and Chinese women in Hawaiʻi correlates with an increase in marriage rates between European men and Asian women in the 1930s.[94] There was a relatively small number of white women in Hawai’i before the Second World War, meaning that they were never “short of options” when it came to marrying within their own racial group.[95] In 1944, only 9% of Caucasian women married men of other races.[96] Although these “out marriage” statistics have been carefully documented in the published historical record, there has been little interest in the unique challenges that these interracial couples and their children faced in what was, in reality, a highly racialised society.

In these RASLR class papers that were selected for preservation in the University Archives, most students explored attitudes towards interracial relationships between Japanese, haole, Chinese, Portuguese, and Filipino men and women. Often, they wrote about their own parents or immediate relatives, such as their aunts and uncles, brothers and sisters, or cousins. In other instances, however, they interviewed members of the public and family friends. The most common narrative to appear is one of strict Japanese parental disapproval of any kind of “out marriage”, although this often resulted in the eventual acceptance of their hapa grandchildren. One mixed-race student, for instance, told the tale of how their “[Japanese] mother’s parents and her sisters and brothers were against [their Filipino father]. They did not speak with him […] one of his in-laws called him ‘Black Filipino’ and ‘Filipino Poke Knife’”. These attitudes changed following their mother’s death and the children’s graduation from high school, with the student reflecting that “since we turned out to be honorable and respectable, stronger relations developed”.[97] On a similar note, a Japanese student explored the gradual “breakdown of racial prejudice” in her family towards her brother’s “Japanese Filipino” wife, who was viewed negatively due to the racial stereotype that Filipinos had awful tempers and carried knives.[98] In an interview with one of the student writers, moreover, a “Japanese-Naichi” woman described how her parents reacted when they discovered she was dating a “Hawaiian-haole” boy:

My father wasn’t too bad, but my mother! She beat me up until I was black and blue. I’m fair so the bruises show more. […] Now you should see the folks. They crazy over my kids”.[99]

Another Japanese student wrote about their aunt, who was estranged from the family after “disgracing” them when she became pregnant with the child of an African American soldier during the Second World War.[100] Fearful of this kind of response from her own parents, one female Japanese student admitted that she stopped dating a haole boy when her mother threatened to disown her.[101]

Similar stories about Chinese adversity to interracial marriage also emerge. Another student recalled “that in her neighbourhood when she was a little girl, a Chinese girl had become involved with a haole. The girl’s widowed mother beat her soundly and finally disowned her […] the names she called her [daughter] were unprintable”. Yet, the student adds that this woman “simply loved her two hapa-haole grandsons and would take them everywhere she went”. Regarding her marriage to a Portuguese man, another Chinese woman recalled in an interview that her mother, who was “especially against the Portuguese, […] was so shame [when she got married] she stayed at home for a whole year”.[102] In additional interviews conducted by this same student, we witness opposition to intermarriage on the Portuguese side. One young Portuguese woman recalled being beaten so severely by her mother that she “thought [her] arm was broken”, which was her punishment for choosing to marry a Puerto Rican man.[103] Perhaps evidence of a generational difference, an elderly Portuguese woman shared with the student interviewer her concern that her own daughter, who was dating a Japanese man, was “going to get slant-eye babies. The eyes going to be so small that he not even going to see good”.[104]

Another essay reveals that, in light of the rise in anti-Japanese sentiments post-Pearl Harbour, a haole serviceman convinced his parents that his Japanese wife was “American Indian” since they “had never seen a Japanese before”.[105] Regarding the haole perspective on interracial marriage in the 1940s, a wealth of information is revealed by the censorship reports produced during the Second World War, which are held at the U.S. National Archives. Letters that were sent to the continent from U.S. servicemen and other haole settlers in Hawaiʻi were moderated by the military censors. These censors, who expressed concerns about maintaining wartime morale, compiled extensive reports containing thousands of excerpts from private wartime letters sent from Hawaiʻi.[106] Many of these letters commented on interracial relationships between white soldiers and local women – the so-called “wartime wedding boom”. John Fox, who arrived in Honolulu in 1944, for example, wrote home saying that “For each soldier one sees with a haole wahine (white girl) on the street, another nine will be seen with oriental girls”. [107] In the fiscal year of 1944, it was recorded that the largest rate (32%) of “out marriages” in Hawaiʻi were among Caucasian men. Mostly, they married “Part Hawaiian” and Japanese women.[108]

These wartime letters state that the white male attitude toward miscegenation changed over time.[109] One man recalled that “When you first arrived in Hawaii [the girls] appeared to be quite dark. However, as the saying went, the longer you were on the island, the lighter those girls became”.[110] Along similar lines, in an article published in the University of Hawaiʻi’s Sociology Department journal Social Process, one man was quoted saying “Since there is an insufficient number of haoles, the dating of Oriental women is not objectionable”.[111] According to Beth Bailey and David Farber’s research, it was haole women and Japanese American women who were most vocal about their opposition to miscegenation in this period, typically blaming each other’s sexual licentiousness. Meanwhile, Native Hawaiian and Filipino women showed the least concern.[112] Some haole men tried their best to convince their families back home that their Japanese or Chinese girlfriends were Americans too.[113] Not everyone took the interracial “wedding boom” seriously, however. Most American observers speculated that these marriages would end in divorce when they returned to the continent.[114] Attitudes towards interracial marriage on the continent remained hostile. In some U.S. states in fact, legislation introduced in August 1944 meant that interracial marriages during the war were nullified, “regardless of whether the marriage was valid when contracted”. Bailey and Farber uncovered the letter of one pregnant Japanese woman who wrote to the Military Governor appealing the decision to deny her the right to marry the father of her child, a white U.S. soldier.[115] Many white Americans refused to believe that these interracial relationships could be anything more than casual wartime flings.[116] Correspondingly, one man wrote home saying that he had “chances to shack up” with local girls, but “wouldn’t want to marry one of them”.[117] Interestingly, it is in these wartime archives that we see the most evidence of casual sexual encounters taking place between different racial groups – which remains a largely neglected aspect of interracial dating history in Hawai’i.

Conclusion

Through exploring real people’s experiences of miscegenation in Hawaiʻi, this research contributes to a growing body of scholarship that seeks to dismantle the myth that Hawaiian society was a “racial paradise” in the early to mid-twentieth century. Although sociological studies written for white audiences on the U.S. continent depicted the high degree of interracial marriage on the islands as an indicator of racial harmony, the unpublished record tells us that interracial unions in this period were often complicated, contested, and painful. Prejudices about interracial dating in Hawaiʻi were multi-directional, and the variety of experiences of both belonging and exclusion that are recorded in the archives remind us that it is unhelpful to make essentialist judgements about the attitudes of different racial groups. Although racial intermixture did not always involve Native Hawaiians, this paper has also demonstrated that the “Part Hawaiian” typology that was created within the social scientific discourse on “hybridity” represented a form of violence that specifically targeted Native people. The “Part Hawaiian” typology was constructed in such a way that haole settlers were able to dispossess Native Hawaiians by safeguarding and policing their indigeneity through blood quantum measurements. By only looking at the construction of “Part Hawaiian” typology “from above”, few historians have acknowledged the great degree of agency that mixed-race Native Hawaiians exhibited when negotiating and formulating their own identities – whether by adopting or rejecting the “Part Hawaiian” classification or reappropriating it through the notion of hapa. Nevertheless, archival sources show us not only that mixed-race people in Hawaiʻi have been the subject of many different layers of stigmatisation, but also that they formed their own prejudices against other groups in the period 1900 to 1960, most notably against Native Hawaiians. This paper has only scratched the surface of this complicated history of miscegenation and mixed-race identity in Hawaiʻi, a topic which certainly deserves greater scholarly attention.

[1] United States Census Bureau, “Race and Ethnicity in the United States: 2010 Census and 2020 Census,” August 12, 2021, www.census.gov/library/visualizations/interactive/race-and-ethnicity-in-the-united-state-2010-and-2020-census.html, accessed 16 April 2022.

[2]Moises Velasquez-Manoff, “Want to Be Less Racist? Move to Hawaii,” The New York Times, June 28, 2019, www.nytimes.com/2019/06/28/opinion/sunday/racism-hawaii.html, accessed April 18, 2022; C. Tanabe, “Educational Policy in the Post-Racial Era: Federal Influence on Local Educational Policy in Hawaiʻi,” Paideusis 19.1 (2010), 59-68; Imani Altemus-Williams and Marie Eriel Hobro, “Hawai’i is not the multicultural paradise some say it is,” National Geographic, May 17, 2021, www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/article/hawaii-not-multicultural-paradise-some-say-it-is, accessed April 18, 2022; Akiemi Glenn, “Want to explore race in Hawai’i? Center those most impacted by it,” Akiemi Glenn (Blog), July 2, 2019, akiemiglenn.net/blog/2019/7/2/2p01kxsurmc9fzkx8jvme7pw0z03bf, accessed April 18, 2022.

[3] Leslie C. Dunn (1893-1974) was a geneticist at Columbia University, who wrote a study on interracial mixing in Hawaiʻi using data collected by Alfred M. Tozzer (see footnote 12). Leslie C. Dunn, “An Anthropometric Study of Hawaiians of Pure and Mixed Blood,” Papers of the Peabody Museum of American Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University, volume 10 (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Peabody Museum, 1928), 91.

[4] Warwick Anderson, “Racial Hybridity, Physical Anthropology, and Human Biology in the Colonial Laboratories of the United States,” Current Anthropology 53.5 (2012), 95-107; Christine Leah Manganaro, “Assimilating Hawaiʻi : Racial Science in a Colonial ‘Laboratory’, 1919-1939,” Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Minnesota, 2012; Maile Arvin, Possessing Polynesians: The Science of Settler Colonial Whiteness in Hawaiʻi and Oceania (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2019).

[5] Camilla Fojas, Rudy P. Guevarra Jr., and Nitasha Tamar Sharma, editors, Beyond Ethnicity: New Politics of Race in Hawaiʻi (Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press, 2018); Mary Bernstein and Marcie De La Cruz, “‘What are you?’: Explaining Identity as a Goal of the Multiracial Hapa Movement,” Social Problems 56.4 (2008), 722-745; Shelley V. Savage,“The Phenomenal Self: Identity Development and Meaning-Making of Mixed-Heritage Adults Born and Raised in Hawai’i,” Ph.D. thesis, The Chicago School of Professional Psychology, 2005; Davor Jedlika, Ethnic serial marriages in Hawaii: application of a sequential preference model (East-West Center, Honolulu: Population Institute: 1998); Xuanning Fu and Tim B. Heaton, Interracial Marriage in Hawaii, 1983-1994 – Mellen Studies in Sociology (Edwin Mellen Press, 1997); Ronald C. Johnson, “Offspring of Cross-Race and Cross-Ethnic Marriages in Hawaii,” in Maria P. P. Root, editor, Racially Mixed People in America (Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications, 1992), 239-249.

[6] Arvin, Possessing Polynesians, 106-111; Manganaro, “Assimilating Hawaiʻi,” 191-237.

[7] Brandon C. Ledward, “Inseparably Hapa: Making and Unmaking a Hawaiian Monolith,” Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Hawaiʻi, 2007.

[8] David Chang, The World and All the Things Upon It: Native Hawaiian Geographies of Exploration (University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis and London, 2016).

[9] Michael Omi and Howard Winant, Racial Formation in the United States, third edition (New York and London: Routledge, 2015), 13.

[10] Robert E. Park, “Our Racial Frontier on the Pacific,” Survey Graphic 9 (1926), 196.

[11] Henry Yu, Thinking Orientals: Migration, Contact, and Exoticism in Modern America (New York: Oxford University Press, 2001), 81.

[12] Specialising in portraiture, American photographer Caroline Haskins Gurrey (1875-1927) ran a photo studio in Honolulu at the start of the twentieth century. Her photo series on Hawaiʻi ’s mixed-race children was exhibited at the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exhibition in Seattle in 1909. A comparable photo series called Hawaiian Types was produced by haole photographer Henry Inn in 1945, which included a foreword from Andrew Lind (see footnote 71). Anne Maxwell, “‘Beautiful Hybrids’: Caroline Gurrey’s Photographs of Hawaii’s Mixed-race Children,” History of Photography 36.2 (2012), 185; “Remarkable photographs of Hawaiian types,” The Hartford Courant 1887 (5 April 1914), X3; Henry Inn, Hawaiian Types (New York: Hastings, 1945).

[13] Alfred M. Tozzer (1877-1954) was an ethnographer and archaeologist. He graduated from Harvard University in 1904 before studying under Franz Boas (“the Father of American anthropology) at Columbia University. He was primarily interested in Mesoamerican studies, but he collected 508 physical anthropometric measurements from Oahu’s multiracial population in the mid-1910s, which he later handed over to Leslie C. Dunn for analysis (see footnote 3); Maxwell, “‘Beautiful Hybrids’,” 195; Anderson, “Racial Hybridity, Physical Anthropology, and Human Biology in the Colonial Laboratories of the United States,” 96; Manganaro, “Assimilating Hawaiʻi,” 62.

[14] Clark Wissler to Henry Fairfield Osborn, 21 September 1920, folder July-September 1920, box 10, Central Archives, American Museum of Natural History, New York, cited in Anderson, “Racial Hybridity, Physical Anthropology, and Human Biology in the Colonial Laboratories of the United States,” 99.

[15] Henry FairfieldOsborn to Louis Robert Sullivan, 17 April 1920, folder April–June 1920, box 10, Central Archives, American Museum of Natural History, New York, cited in Anderson, “Racial Hybridity, Physical Anthropology, and Human Biology in the Colonial Laboratories of the United States,” 95.

[16] Leslie C. Dunn quoted in Anderson, “Racial Hybridity, Physical Anthropology, and Human Biology in the Colonial Laboratories of the United States,” 97.

[17] At the University of Chicago, Romanzo Adams (1868-1942) completed his graduate studies under Robert E. Park (see footnote 34). After receiving his Ph.D. in 1904, Adams worked as a teacher in Iowa. In 1919, he founded the Sociology Department at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa and became their first Professor of Sociology and Economics, a position that he held until his retirement in 1934. In 1926, he founded the Sociology Department’s Station for Racial Research (funded by the Rockefeller Foundation), which made thorough efforts to document interracial mixing on the islands. In 1955, the research station was renamed the Romanzo Adams Social Research Laboratory (RASLR) in his honor. Romanzo Adams “The Study of Race Relations in Hawaii” (1931), folder 7, box 1, series 214S, RG 1.1, Rockefeller Foundation Archives, RAC, 2, cited in Manganaro, “Assimilating Hawaiʻi,” 138; University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa,“Biographical Sketch of Romanzo Adams and History of the Romanzo Adams Social Research Laboratory,” https://manoa.hawaii.edu/library/research/collections/archives/university-archives/colleges-schools-research-institutes-etc/romanzo-adams-social-research-laboratory/biographical-sketch-of-romanzo-adams-and-history-of-the-romanzo-adams-social-research-laboratory/, accessed April 20, 2022.

[18] David G. Croly, et al., Miscegenation; the theory of the blending of the races, applied to the American white man and negro (New York: H. Dexter, Hamilton & Co., 1864).

[19] Peggy Pascoe, What Comes Naturally: Miscegenation Law and the Making of Race in America (Oxford University Press, 2010); W.E.B. Du Bois, “Miscegenation” [1930], in Against racism: Unpublished essays, papers, addresses, 1887-1961, by W.E.B. Du Bois, edited by Herbert Aptheker (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1980), 90-102.

[20] Maxwell, “‘Beautiful Hybrids’,” 190.

[21] M. Billinger, “Degeneracy,” Eugenics Archive (online), 2014, http://eugenicsarchive.ca/discover/tree/535eeb0d7095aa0000000218h, accessed April 23, 2022.

[22] New York-based lawyer and zoologist Madison Grant (1865-1937) is best known for his work as a eugenicist and advocate of scientific racism. He was an influential member of the American Eugenics Society, Galton Society, the International Committee of Eugenics, and the U.S. Immigration Restriction League. Madison Grant, The Passing of the Great Race: Or, the Racial Basis of European History (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, fourth edition, 1936) [1916], 60.

[23] An unusual exception to the eugenic discourse on the preservation of the white race came from Uldrick Thompson (1849-1942) a haole schoolteacher at Kamehameha Boys’ School. In 1913 and 1915, Thompson created eugenics pamphlets for his Native Hawaiian students and their parents in which he lamented the degeneration of the Native Hawaiian race and promoted “purer” unions between them. Uldrick Thompson, “Eugenics for Parents and Teachers,” 1915; Uldrick Thompson, “Eugenics for Young People,” 1913; Billinger, “Degeneracy”.

[24] An Act to Preserve Racial Integrity, Virginia, 1924, www2.vcdh.virginia.edu/lewisandclark/students/projects/monacans/Contemporary_Monacans/racial.html.

[25] American physical anthropologist Earnest A. Hooton (1887-1954) pursued his graduate studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and the University of Oxford, England before taking a four-decade long teaching position at Harvard University. He is best known for his work on racial classification and his popular publications such as Up From the Ape (1931) and Apes, Men, and Morons (1937). Ernest A. Hooton (1926) quoted in Anderson, “Racial Hybridity, Physical Anthropology, and Human Biology in the Colonial Laboratories of the United States,” 98.

[26] Alfred M. Tozzer, “The Anthropology of the Hawaiian Race,” in Proceedings of the First Pan-Pacific Science Conference, Under the Auspices of the Pan Pacific Union, Honolulu, Hawaii, August 2 to 20, 1920: Part I (Honolulu: Honolulu Star-Bulletin, 1921), 70-74.

[27] Nevertheless, American onlookers who continued to harbor anti-Black and anti-Asian prejudices simply dismissed Hawaiʻi as “a failed experiment where the color line had been irretrievably breached”. Shelley Shang-Hee Lee and Rick Baldoz, “‘A Fascinating Interracial Experiment Station’: Remapping the Orient-Occident Divide in Hawai’i,” American Studies 49.3-4 (2008), 100.

[28] Dunn, “An Anthropometric Study of Hawaiians of Pure and Mixed Blood,” 176.

[29] Frederick L. Hoffman, “Miscegenation in Hawaii.” Journal of heredity 8.1 (1917), 12.

[30] After graduating from Princeton University and Bellevue Medical School of New York, palaeontologist and eugenicist Henry Fairfield Osborn (1857-1930) trained under Thomas Huxley and Francis Maitland Balfour at the University of Cambridge, England. Holding teaching positions in anatomy and zoology at Princeton and Columbia University respectively, Osborn also served as President of the American Museum of Natural History from 1909 to 1925. Following a visit to Hawaiʻi c.1920, he instructed Louis R. Sullivan to conduct studies into multiracialism on the islands. Manganaro, “Assimilating Hawaiʻi,”65; Osborn to Sullivan, 7 July 1920, folder April-June 1920, box 10, Central Archives, American Museum of Natural History, New York, cited in Anderson, “Racial Hybridity, Physical Anthropology, and Human Biology in the Colonial Laboratories of the United States,” 95.

[31] Romanzo Adams, Interracial Marriage in Hawaii: A Study of the Mutually Conditioned Process of Acculturation and Amalgamation (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1937); University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa,“Biographical Sketch of Romanzo Adams”; Arvin, Possessing Polynesians, 97; Sidney Gulick, Mixing the Races in Hawaii: A Study of the Coming of the Neo-Hawaiian American Race (Honolulu: Hawaiian Board Book Rooms, 1937); John Chock Rosa, “‘The Coming of the Neo-Hawaiian American Race’: Nationalism and Metaphors of the Melting Pot in Popular Accounts of Mixed-Race Individuals,” in Mixed-Heritage Asian Americans, edited by Teresa Williams-Leon and Cynthia L. Nakashima (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2001), 51.

[32] Anderson, “Racial Hybridity, Physical Anthropology, and Human Biology in the Colonial Laboratories of the United States,” 100.

[33] Arvin, Possessing Polynesians, 94.

[34] American urban sociologist Robert E. Park (1864-1944) received his degrees from the University of Minnesota, University of Michigan, and Harvard University. He taught at the latter before joining the Sociology Department at the University of Chicago from 1914 until 1933. In the early 1930s, he held a 12-month position as a guest lecturer at the University of Hawaiʻi. Robert E. Park, “Mentality of Racial Hybrids,” American Journal of Sociology 36.4 (1931), 534-551.

[35] Jayne O. Ifekwunigwe, editor, “Mixed Race” Studies: A Reader (London and New York: Routledge, 2004), 8; Omi and Winant, Racial Formation in the United States, 13.

[36] “Mixed race” nevertheless continues to be used as a racial category today. As recently as 2021, the US Census Bureau published a resource that lumped together the 33.8 million mixed-race people of the United States into the single category of “two or more races”. United States Census Bureau, “Race and Ethnicity in the United States: 2010 Census and 2020 Census”; Nicholas Jones, et al. “Improved Race and Ethnicity Measures Reveal U.S. Population is Much More Multiracial,” United States Census Bureau, 12 August 2020 www.census.gov/library/stories/2021/08/improved-race-ethnicity-measures-reveal-united-states-population-much-more-multiracial.html.

[37] C.K. Cheng and Douglas S. Yamamura, “Interracial Marriage and Divorce in Hawaii,” Social Forces 30.1 (1957), 77-84; Ralph Kuykendall, The Hawaiian Kingdom, 1778-1854 (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1938), 25; Andrew Lind, Hawaii’s People, fourth edition (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, [1955] 1980), 6.

[38] Adams, Interracial Marriage in Hawaii, 21-22.

[39] I have not yet encountered an early example of the term “Part Hawaiian” being used.

[40] “Hawaiʻi – Census 1866 Enumeration Sheets,” Hawaiian Kingdom Census, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, Hawaiian and Pacific Collection, https://guides.library.manoa.hawaii.edu/hawaiicensus1866; “Hawaiʻi – Census 1878 Enumeration Sheets,” Hawaiian Kingdom Census, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, Hawaiian and Pacific Collection, https://guides.library.manoa.hawaii.edu/hawaiicensus1878; “Hawaiʻi – Census 1890 Enumeration Sheets,” Hawaiian Kingdom Census, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, Hawaiian and Pacific Collection, https://guides.library.manoa.hawaii.edu/hawaiicensus1890.

[41] Adams, Interracial Marriage in Hawaii, 23.

[42] C.K. Cheng and Douglas S. Yamamura, ‘Interracial Marriage and Divorce in Hawaii,’ Social Forces 30.1 (1957), 77-84; Adams, Interracial Marriage in Hawaii, p.76.

[43] Dunn, “An Anthropometric Study of Hawaiians of Pure and Mixed Blood,” 152.

[44] A report published in 1917 recorded that out of the 210 haole grooms who married in Hawaiʻi in 1914, only 53.3% married haole women. 11.9% married “Caucasian-Hawaiian women”, and 5.2% married “full-blood Hawaiian women”. 1.9% married “Chinese-Hawaiian women”; 1.4% “full-blood Chinese women”; 1.9% “Porto-Rican women”; and the remainder had wed British, Filipino, French, German, Japanese, Mexican-Portuguese, Norwegian, Spanish and Swedish women. “Miscegenation in Hawaii,” Journal of heredity 8.1 (1917), 12.

[45] Although the 1900 U.S. Census does not include a list of possible race options, census administrators used the shorthand “PH” to denote “Part Hawaiians” in the “race” column of the form. 1900 U.S. Census Records https://www.familysearch.org/search/collection/1325221; E. Dana Durand and WM. J. Harris, Thirteenth Census of the United States Taken in the Year 1910: Statistics for Hawaiʻi (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1913), 9.

[46] Durand and Harris, Thirteenth Census of the United States Taken in the Year 1910, 9; 1910 U.S. Census Records.

[47] The multiracial category “Mulatto” was used in the U.S. continent, but it does not appear to have been used in Hawaiʻi given the small size of the African American population on the islands. United States Census Bureau, “Measuring Race and Ethnicity Across the Decades,” 2010, https://www.census.gov/data-tools/demo/race/MREAD_1790_2010.html.

[48] 1940 U.S. Census Records, https://www.familysearch.org/search/collection/2000219.

[49] It was specified that a person with one Caucasian and one non-Caucasian parent should be listed as the race of their non-Caucasian parent. Lind, Hawaii’s People, 11; 1950 U.S. Census Records https://www.familysearch.org/search/collection/4464515.

[50] Karen R. Humes et al., “Overview of Race and Hispanic Origin: 2010,” U.S. Census Bureau: 2010 Census Briefs, March 2011, www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-02.pdf.

[51] The term “Part Hawaiian” was not used in the U.S. Census after 1960. Kim Parker, et al. “Race and Multiracial Americans in the U.S. Census,” Pew Research Center, June 11, 2015, https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2015/06/11/chapter-1-race-and-multiracial-americans-in-the-u-s-census/; United States Census Bureau, “Measuring Race and Ethnicity Across the Decades,” 2010, https://www.census.gov/data-tools/demo/race/MREAD_1790_2010.html.

[52] Louis R. Sullivan worked as the assistant curator of physical anthropology at the American Museum of Natural History for two years before he was appointed to work with the Bishop Museum in 1920. He received training from both Charles Davenport and Franz Boas. Sullivan concluded that there were two original racial types of Polynesian – “The Polynesians of Polynesia” and the “Indonesians of Polynesia”. Louis R. Sullivan, “New Light on the Races of Polynesia,” Asia, January 1923 andLouis Robert Sullivan to Herbert Gregory, June 22, 1922 cited in Arvin, Possessing Polynesians, 80-85; Charles Benedict Davenport, Scientific Papers of the Second International Congress of Eugenics Held at American Museum of Natural History, New York, September 22–28, 1921 (Baltimore: Williams and Williams, 1923), 484; Manganaro, “Assimilating Hawaiʻi,” 37.

[53] Louis R. Sullivan and Clark Wissler, Observations on Hawaiian Somatology (Honolulu: Bishop Museum Press, 1927).

[54] Sullivan likely used skeletal material from Molokaʻi and Lanai gathered by Bishop Museum employees who desecrated Native Hawaiian graves. One of these employees was Kenneth Emory, who wrote in a letter in 1923 that Bishop Museum officials had excluded details of his taboo activities from their official records. Kenneth Emory to Louis Sullivan, August 20, 1923; Folder: Fibial – Descriptions and Measurements, Box: Sullivan, Louis Robert, Hawaiian Data Sheets, Anthropometric Studies, Division of Anthropology, AMNH, cited in Manganaro, “Assimilating Hawaiʻi,” 62.

[55] Anderson, “Racial Hybridity, Physical Anthropology, and Human Biology in the Colonial Laboratories of the United States,” 99.

[56] Maxwell, “‘Beautiful Hybrids’,” 191.

[57] Arvin, Possessing Polynesians, 77.

[58] Lee and Baldoz, “‘A Fascinating Interracial Experiment Station’,” 100.

[59] Louis R. Sullivan quoted in Anderson, “Racial Hybridity, Physical Anthropology, and Human Biology in the Colonial Laboratories of the United States,” 100.

[60] Adams, Interracial Marriage in Hawaii, 233.

[61] William A. Lessa was a New Jersey-born Italian American student enrolled at Harvard University. He later became Professor, Emeritus of Anthropology at the University of California at Los Angeles. Online Archives of California, “William A. Lessa, Anthropology: Los Angeles” http://texts.cdlib.org/view?docId=hb267nb0r3&doc.view=frames&chunk.id=div00033&toc.depth=1&toc.id=; Anderson, “Racial Hybridity, Physical Anthropology, and Human Biology in the Colonial Laboratories of the United States,” 101.

[62] William A. Lessa to Harry Shapiro, 4 August 1931, folder William Lessa, box 2, Shapiro papers and William A. Lessa to Harry Shapiro, 14 October 1930, folder 1930, box 3, Shapiro papers, cited in Anderson, “Racial Hybridity, Physical Anthropology, and Human Biology in the Colonial Laboratories of the United States,” 102.

[63] Margaret Lam’s interviews with “Chinese Hawaiians” 1930-1931, box labelled “Anthropo-social data 1930-1931”, RASLR Collection, University of Hawaiʻi Archives. Unclear if Doris Lorden was also involved in conducting these interviews. Hereafter cited as “Lam Interview”.

[64] Arvin, Possessing Polynesians, 22.

[65] Lam Interview #49.

[66] Lam Interview #2.

[67] Lam Interview #21.

[68] William A. Lessa to Harry Shapiro, 14 October 1930, folder 1930, box 3, Shapiro papers, cited in Anderson, “Racial Hybridity, Physical Anthropology, and Human Biology in the Colonial Laboratories of the United States,” 102.

[69] William A. Lessa to Harry Shapiro, 11 November 1930, folder 1930, box 3, Shapiro papers, cited in Anderson, “Racial Hybridity, Physical Anthropology, and Human Biology in the Colonial Laboratories of the United States,” 102.

[70] Adams, Interracial Marriage in Hawaii, 14.

[71] Andrew W. Lind (1901-1988) came to the University of Hawaiʻi’s Sociology Department in 1927 after completing his doctorate work at the University of Chicago. A contemporary of Romanzo Adams, he took over as director of the Hawaii Social Research Laboratory (RASLR) from 1934 until 1961. Lind, Hawaii’s People, 121.

[72] As early as 1880, Swedish ethnologist Abraham Fornander had portrayed the “Polynesian Race” as having mixed ancestry. Adams, vii. Abraham Fornander and John F.G. Stokes, An Account of the Polynesian Race, Its Origins and Migrations, and the Ancient History of the Hawaiian People to the times of Kamehameha I (London: Trubner, 1880).

[73] Lind, Hawaii’s People, 121.

[74] J. Kēhaulani Kauanui, Hawaiian Blood: Colonialism and the Politics of Sovereignty and Indigeneity (Duke University Press, 2008), 15.

[75] Kauanui, Hawaiian Blood, 11.

[76] Arvin, Possessing Polynesians, 22.

[77] Arvin, Possessing Polynesians, 94.

[78] Kauanui, Hawaiian Blood, 15.

[79] Ledward, “Inseparably hapa”, 26.

[80] Ledward, “Inseparably hapa”, 65-66.

[81] Ledward, “Inseparably hapa”, 67.

[82] Arvin, Possessing Polynesians, 105.

[83] Lam Interview, #12

[84] Lam Interview, #15

[85] Lam Interviews #80, #86, #78.

[86] Lam Interview #25.

[87] Manganaro, “Assimilating Hawaiʻi,” 233.

[88] Arvin, Possessing Polynesians, 23.

[89] Adams, Interracial Marriage in Hawaii, 22.

[90] Bernhard L. Hörmann, “Racial Complexion of Hawaiʻi ’s Future Population,” Social Forces 27.1 (1948-1949), 70.

[91] Joan Hori, “Japanese Prostitution in Hawaii during the Immigration period,” Hawaiian Journal of History 15 (1981), 113-124.

[92] Miyaoka Kanichi, Kaigai Ruroki [Account of Overseas Travels] (Tokyo: Shanichi Shobo, 1968), 188-119, cited in Hori, “Japanese Prostitution in Hawaii during the Immigration period,” 118.

[93] Hori, “Japanese Prostitution in Hawaii during the Immigration period,” 114-115; Adams, Interracial Marriage in Hawaii, 20.

[94] Adams, Interracial Marriage in Hawaii, 23-24.

[95] Jonathan Y. Okamura, Ethnicity and Inequality in Hawai’i (Philadelphia, Temple University Press 2008), 33.

[96] Beth Bailey and David Farber, The First Strange Place: Race and Sex in World War II Hawaiʻi (The John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore and London, 1992), 194-195.

[97] “My Father’s Marriage”, December 13, 1961, “Papers written on Interracial Marriage or Dating,” Fall 1961, sec. 1 (RASPC Student Papers Box 6), University of Hawaiʻi Archives.

[98] “The Breakdown of Racial Prejudice in my Home,” December 2, 1960, “Papers written on Interracial Marriage or Dating,” Fall 1960, sec. 1, (RASPC Student Papers Box 6), Folder 18, University of Hawaiʻi Archives.

[99] “Race Prejudice in Hawaii,” “Papers written on Interracial Marriage or Dating,” Fall 1961, sec. 1 (RASPC Student Papers Box 6), University of Hawaiʻi Archives.

[100] “The Effects of Interracial Marriage,” December 2, 1960, “Papers written on Interracial Marriage or Dating,” Fall 1960, sec. 1, (RASPC Student Papers Box 6), Folder 18, University of Hawaiʻi Archives.

[101] “Race Prejudice in Dating and Marriage”, December 2, 1960, “Papers written on Interracial Marriage or Dating,” Fall 1960, sec. 1, (RASPC Student Papers Box 6), Folder 18, University of Hawaiʻi Archives.

[102] “Race Prejudice in Hawaii.”

[103] “Race Prejudice in Hawaii.”

[104] “Race Prejudice in Hawaii.”

[105] “Racial Prejudice in Dating and Marriage.”

[106] Bailey and Farber, The First Strange Place, 192.

[107] John Fox, letter to “mainland friends,” August 22, 1944, cited in Bailey and Farber, The First Strange Place, 193.

[108] Bailey and Farber, The First Strange Place, 194-195. Otome Inamine, et al., “The Effect of War on inter-Racial Marriage in Hawaii,” Social Process in Hawaii 9-10 (July 1945), 103-109.

[109] Bailey and Farber, The First Strange Place, 192-193.

[110] Howard W. Muthin, 1991, cited in Bailey and Farber, The First Strange Place, 193.

[111] Dorothy Jim and Takiki Takiguchi, “Attitudes on Dating Oriental Girls with Servicemen,” Social Process in Hawaii 8 (November 1943), 69.

[112] Censorship Reports, box V9375, A8-5/LL, cited in Bailey and Farber, The First Strange Place, 197-198.

[113] Censorship Records, LL-3, 9/15-30/43, 11, cited in Bailey and Farber, The First Strange Place, 195.

[114] Bailey and Farber, The First Strange Place, 195; Takiguchi, “Attitudes on Dating Oriental Girls with Servicemen,” 69.

[115] Bailey and Farber, The First Strange Place, 196.

[116] Bailey and Farber, The First Strange Place, 194; Takiguchi, “Attitudes on Dating Oriental Girls with Servicemen,” 69.

[117] Censorship Reports LL-4, 5/1-15/44, 9, cited in Bailey and Farber, The First Strange Place, 193.

Bibliography

Archives:

RASLR Collection, University of Hawaiʻi Archives

Hawaiʻi Kingdom Census Data 1866-1890

U.S. Census Data 1900-1960

Published sources:

“Remarkable photographs of Hawaiian types.” The Hartford Courant 1887 (5 April 1914).

Adams, Romanzo. Interracial Marriage in Hawaii: A Study of the Mutually Conditioned Process of Acculturation and Amalgamation. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1937.

Alfred M. Tozzer, “The Anthropology of the Hawaiian Race,” in Proceedings of the First Pan-Pacific Science Conference, Under the Auspices of the Pan Pacific Union, Honolulu, Hawaii, August 2 to 20, 1920: Part I. Honolulu: Honolulu Star-Bulletin, 1921.

Altemus-Williams, Imani and Marie Eriel Hobro. “Hawai’i is not the multicultural paradise some say it is.” National Geographic. May 17, 2021. www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/article/hawaii-not-multicultural-paradise-some-say-it-is. Accessed April 18, 2022.

Anderson, Warwick. “Racial Hybridity, Physical Anthropology, and Human Biology in the Colonial Laboratories of the United States.” Current Anthropology 53.5 (2012), 95-107.

Aptheker, Herbert, editor. Against racism: Unpublished essays, papers, addresses, 1887-1961, by W.E.B. Du Bois. University of Massachusetts Press, 1980.

Arvin, Maile. Possessing Polynesians: The Science of Settler Colonial Whiteness in Hawaiʻi and Oceania. Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2019.

Bailey, Beth and David Farber. The First Strange Place: Race and Sex in World War II Hawaii. The John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore and London, 1992.

Bernstein, Mary and Marcie De La Cruz. “‘What are you?’: Explaining Identity as a Goal of the Multiracial Hapa Movement.” Social Problems 56.4 (2008), 722-745.

Billinger, M., “Degeneracy.” Eugenics Archive (online). 2014. http://eugenicsarchive.ca/discover/tree/535eeb0d7095aa0000000218h. Accessed April 23, 2022.

Croly, David G. et al., Miscegenation; the theory of the blending of the races, applied to the American white man and negro. New York: H. Dexter, Hamilton & Co., 1864.

Chang, David. The World and All the Things Upon It: Native Hawaiian Geographies of Exploration. University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis and London, 2016.

Cheng, C. K. and Douglas S. Yamamura. “Interracial Marriage and Divorce in Hawaii.” Social Forces 30.1 (1957), 77-84.

Davenport, Charles Benedict. Scientific Papers of the Second International Congress of Eugenics Held at American Museum of Natural History, New York, September 22–28, 1921. Baltimore: Williams and Williams, 1923.

Dunn, Leslie C. “An Anthropometric Study of Hawaiians of Pure and Mixed Blood,” Papers of the Peabody Museum of American Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University, volume 10. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Peabody Museum, 1928.

Durand, E. Dana and WM. J. Harris, Thirteenth Census of the United States Taken in the Year 1910: Statistics for Hawaiʻi . Washington: Government Printing Office, 1913.

Fojas, Camilla, Rudy P. Guevarra Jr., and Nitasha Tamar Sharma, editors. Beyond Ethnicity: New Politics of Race in Hawaiʻi. Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press, 2018.

Fornander, Abraham and John F.G. Stokes. An Account of the Polynesian Race, Its Origins and Migrations, and the Ancient History of the Hawaiian People to the times of Kamehameha I. London: Trubner, 1880.

Fu, Xuanning and Tim B. Heaton. Interracial Marriage in Hawaii, 1983-1994 – Mellen Studies in Sociology. Edwin Mellen Press, 1997.

Glenn, Akiemi. “Want to explore race in Hawai’i? Center those most impacted by it.” Akiemi Glenn (Blog).July 2, 2019. akiemiglenn.net/blog/2019/7/2/2p01kxsurmc9fzkx8jvme7pw0z03bf. Accessed April 18, 2022.

Grant, Madison. The Passing of the Great Race: Or, the Racial Basis of European History. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, fourth edition, 1936 [1916].

Gulick, Sidney. Mixing the Races in Hawaii: A Study of the Coming of the Neo-Hawaiian American Race. Honolulu: Hawaiian Board Book Rooms, 1937.

Hoffman, Frederick L. “Miscegenation in Hawaii.” Journal of heredity 8.1 (1917), 12.

Hori, Joan. “Japanese Prostitution in Hawaii during the Immigration period.” Hawaiian Journal of History 15 (1981), 113-124.

Hörmann, Bernhard L. “Racial Complexion of Hawaiʻi ’s Future Population.” Social Forces 27.1 (1948-1949), 68-72.

Humes, Karen R. et al. “Overview of Race and Hispanic Origin: 2010.” U.S. Census Bureau: 2010 Census Briefs. March 2011. www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-02.pdf.

Ifekwunigwe, Jayne O., editor. “Mixed Race” Studies: A Reader. London and New York: Routledge, 2004.

Inamine, Otome, et al. “The Effect of War on inter-Racial Marriage in Hawaii.” Social Process in Hawaii 9-10 (July 1945), 103-109.

Inn, Henry. Hawaiian Types. New York: Hastings, 1945.

Jedlika, Davor. Ethnic serial marriages in Hawaii: application of a sequential preference model. East-West Center, Honolulu: Population Institute: 1998.

Jim, Dorothy and Takiki Takiguchi. “Attitudes on Dating Oriental Girls with Servicemen.” Social Process in Hawaii 8 (November 1943), 66-76.

Jones, Nicholas et al. “Improved Race and Ethnicity Measures Reveal U.S. Population is Much More Multiracial.” United States Census Bureau, 12 August 2020. www.census.gov/library/stories/2021/08/improved-race-ethnicity-measures-reveal-united-states-population-much-more-multiracial.html.

Kauanui, J. Kēhaulani. Hawaiian Blood: Colonialism and the Politics of Sovereignty and Indigeneity. Duke University Press, 2008.

Kuykendall, Ralph. The Hawaiian Kingdom, 1778-1854. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1938.

Laughlin, Harry. The Second International Exhibition of Eugenics: An Account of the Organization of the Exhibitors, and a Catalogue and Description of the Exhibits, volumes 1 and 3. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins Company, 1923.

Ledward, Brandon C. “Inseparably Hapa: Making and Unmaking a Hawaiian Monolith.” Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Hawaiʻi, 2007.

Lind, Andrew. Hawaii’s People, fourth edition. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, [1955] 1980.

Manganaro, Christine Leah. “Assimilating Hawaiʻi : Racial Science in a Colonial ‘Laboratory’, 1919-1939.” Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Minnesota, 2012.

Maxwell, Anne. “‘Beautiful Hybrids’: Caroline Gurrey’s Photographs of Hawaii’s Mixed-race Children.” History of Photography 36.2 (2012), 184-198.

Office of Hawaiian Affairs (OHA), Research Division Demography Section. Native Hawaiian Population Enumerations in Hawaiʻi. Honolulu: May 2017. https://19of32x2yl33s8o4xza0gf14-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/uploads/RPT_Native-Hawaiian-Population-Enumerations.pdf.

Okamura, Jonathan Y. Ethnicity and Inequality in Hawai’i. Philadelphia, Temple University Press 2008.