Introduction

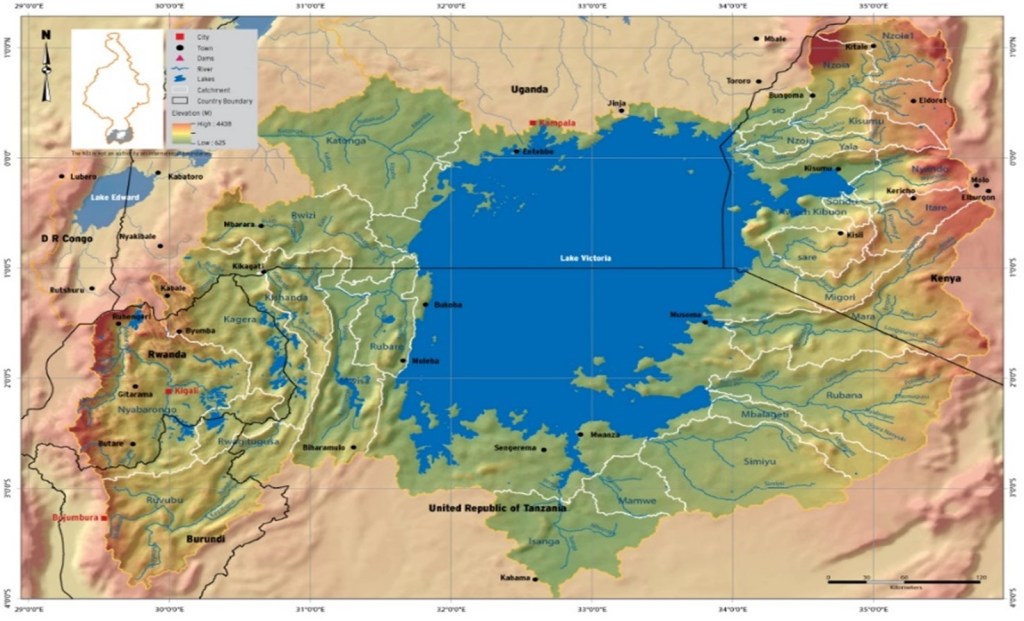

In July 1858, English explorer John H. Speke became the first European to set eyes on the source of the River Nile, a large inland body of water located in East Africa that he called “Victoria Nyanza” in honour of the United Kingdom’s Queen.[1] Whilst Western authors glorified Speke’s “discovery” and treated European exploration as the chronological starting point of Africa’s history, the significance of these waters for East African societies long predates European interest in the region.[2] As early as the thirteenth century, Lake Victoria attracted communities to settle in and around its basin (Figure 1).[3] The Luo invaded what is now Uganda and then Kenya from North Africa via the River Nile, whilst the lake’s Bantu migrants of Baganda, Bunyoro, Ankole, Basoga, and Toro came from Central Africa. Meanwhile, the Lake’s southern shores in modern-day Tanzania came to be dominated by the Sukuma and Nyamwezi.[4] Rethinking the narrative of British “discovery” in Africa, this paper examines how British colonial interventions destabilised traditional subsistence relationships between Lake Victoria and its surrounding communities. Using the interdisciplinary methodologies of “Water History”, I trace changes in the farming and fishing practices of three tribes on Lake Victoria’s shores from the mid-nineteenth century through to the present day: namely, the Luo of Western Kenya’s Nyzanza Province, the Sukuma of Mwanza in Northwestern Tanzania, and the Basoga of Busoga Kingdom in Southern Uganda near Jinja. My intention is not to provide a comprehensive account of these communities and the great diversities that exist among and between them, but to offer a broad view of how Africans have explored these waters and some of the ways in which colonialism disrupted the social, economic, and spiritual connections between the shore-folk and the lake.

Due to foreign interest in the economic potential of the Nile perch fish that was introduced to Lake Victoria in the 1950s, detailed literature already exists on the history of fishing in the region. Scholars, however, have paid relatively little attention to the fact that Lake Victoria’s shore-folk did not simply rely on water for fishing, but for agriculture and interrelated cultural and spiritual practices too. A challenge of this research is that information about the Luo, Sukuma, and Basoga’s relationships with Lake Victoria is sparse within the written historical record. Pockets of information about each of these tribes is scattered throughout European colonial travel accounts and anthropological texts from the nineteenth and twentieth century, but it must be noted that these books were often explicitly racist, having emphasised the “ugliness” and “inferiority” of the so-called “negro tribes” of Lake Victoria. A few more recent environmental conservation and development-focused case studies have been published concerning these communities in the late-twentieth and early twenty-first century, yet no such study has traced the history of any one of these tribes’ relationships with water over time.

Prior to British rule, the waters of Lake Victoria were used in a variety of different ways by the Luo, Sukuma, and Basoga in order to sustain their interdependent livelihoods of farming and fishing in accordance with their spiritual and cultural beliefs. They relied on the lake for local tilapia fish, which was the main protein in their diet and a valuable commodity. Moreover, their agriculture did not use irrigation channels so they were completely reliant on the basin’s rains, which each of these tribes believed could be influenced through their own particular rainmaking practices. Today, the relationship between these tribes and the water are markedly different, with water-based livelihoods having become increasingly unstable and unreliable since the arrival of the British. What follows is a discussion of the impacts of several colonial-era developments on these peoples and their practices, including the control and commercialization of the fishing industry and its expansion to world markets; the introduction of the invasive Nile perch fish species, which irreversibly changed the ecology of the lake after the 1950s; flood prevention schemes and the introduction of new flora; and urbanization trends which led to the building of hydropower dams after 1947.

The Lake Victoria Basin

Shared between Kenya (6%), Uganda (45%), and Tanzania (49%), Lake Victoria basin (LVB) is one of the most population dense rural areas in the world today, supporting the livelihoods of over 42 million people (Figure 2).[5] The lake acts as Africa’s largest inland fishery, with over 1 million fishers and fish-sellers operating on its waters. At present, fishing is the most important economic activity in the region. Lake Victoria currently produces up to 500,000 metric tons of fish a year, with Tanzania accounting for 40% of the annual catch, Kenya 35%, and Uganda 25%.[6] The lake’s waters are also used for energy, transport, irrigation, and domestic and livestock purposes.[7] The size of the entire drainage basin is 258,000km2, which extends to Rwanda and Burundi and includes 212 lake islands, 150 of which are inhabited.[8]

With a surface area of 68,800km2, Lake Victoria is Africa’s largest lake and the second largest inland body of freshwater in the world.[9] Although its surface area is large, with its greatest length measuring approximately 400km, Lake Victoria is relatively shallow.[10] The lake supports a rich ecosystem including the extraordinarily diverse cichlid fish species, whilst its wetlands are known for their biodiversity.[11] Although Lake Victoria has 17 tributaries, these only supply about 13% of the water that enters the lake. The rest is from rainfall, meaning that water levels depend almost entirely on precipitation rates. LVB receives a reasonably generous annual rainfall that averages between 1200 and 1600mm, although the Kenyan part of the basin is the wettest (Figure 3).[12] There are no remarkably dry months in the year but there are two annual rainy seasons, a longer season from around March to June and shorter one from October to December, which provide essential rains for agriculture. LVB is more prone to climate extremes than neighboring areas, however, and climatic variations in rainfall directly impact food security in the region.[13]

Scientists have measured several drastic changes in the ecological character of LVB in the past fifty years, including deep water deoxygenation, changing algal species, changing water levels, deforestation, erosion, and lake eutrophication.[14] Today, Tanzania, Kenya, and Uganda are all grappling with the interrelated issues of population growth, famine, poverty, drought, pollution, economic decline, resource-depletion and overfishing in the region. Given their shared colonial experience under British rule (Uganda was a British protectorate 1894-1962, Kenya became a British protectorate in 1895 before it was designated a Crown Colony 1920-1963, and Tanganyika was a British mandate 1920-1961), the question lingers whether the troubles facing the region today are a legacy of the management of the lake’s resources under the British Empire.

Farming and fishing practices before 1800

Long predating the arrival of Europeans, Africans explored Lake Victoria as part of their broader efforts to build relationships with the environment and manage their water and subsistence needs. Village cultures around Lake Victoria in 1850 centred on fishing, crop production, livestock, and craft.[15] Fishing was usually a male-dominated communal activity in this period, and it centered on the local Singida tilapia fish Oreochromis esculentus (known in Kenya and Uganda as ngege and in Tanzania as furu), of the cichlid species which formed 80% of the lake’s fish at this time. Other important although less abundant fish for these communities included the Oreochromis variabilis (Victoria tilapia), Labeo victorianus (ray-finned fish), synoditis victoriae (Lake Victoria squeaker), mormmyrus kanume (elephant-snout fish), and catfish.[16] Traps had to be set in the early hours of the morning and required the labour of multiple people. With only a small number of canoes operating on the waters, moreover, each boat would hold at least five fishers, who set up nets either together or individually.[17] Among the Luo, the day’s catch was divided between the whole group, with the owner of the canoe receiving 10% as compensation for providing the transport.[18] Fishing practices were well-advanced and adapted to suit different species. Traditional papyrus nets could catch hundreds of fish in a relatively short amount of time, and the Luo used lines, hooks, nets, traps, baskets made from papyrus reeds, and spears.[19] Among the Sukuma, to whom Lake Victoria was known as “Sukuma Lake”, fishing was carried out extensively on the shores of Mwanza Gulf and in the Sumyu and Duma rivers using fishing hooks, long rods, nets, and weir baskets in which fish would enter through a small opening (Figure 4).[20] Fresh, smoked, or dried, any surplus ngege was usually sold by women at the local markets or in huts set up on the beach. Fishers operated as fraternities within local exchange networks, establishing long-lasting personal trading links around the basin.[21]

Traditionally, the Luo were an agricultural and fishing community who referred to themselves as Jo Nam, meaning “the people of lakes and rivers.”[22] Prior to European arrival, the Luo were organised into around twelve patrilineal ogendini (clans) varying from 10,000-70,000 people. Each oganda (clan, singular) was its own independent economic and political unit headed by a hierarchy ofiguf chiefs and a council of Jodong Dhoot (clan elders).[23] Fishing was an art as much as an occupation, with the Luo being highly specialised in river, mud, wetland, and lakeshore fishing. As revealed in an oral history conducted by Paul Opondo, Luo fishers operated within their own clan-based communities in the pre-colonial period, and developed highly effective conservation measures to protect the lake’s ecology and ensure a plentiful supply of fish, which was an essential foodstuff for their people and also a locally valued commodity.[24] Lake Victoria is better known in the Dholuo language as Nam Lolwe, which translates as “endless body of water.”[25] The Jo Lupo (fishers) practiced “free access” to the lake, meaning that there were no formal regulations about who could be a fisher, although the elders enforced strict regulations about when fishing could take place and what mesh-size could be used on fishing nets. To allow for breeding and to protect eggs and juvenile fish, there was a closed season between February and June when chike-lupo (fishing) was restricted by the elders and canoes were only allowed to go a certain distance into the lake.[26] During the fish breeding season, the Luo would work on their farms, primarily growing cereal crops, sorghum, cassava, and millet.[27] In this way, farming and fishing were interdependent activities, whilst communities at the edge of the basin that exclusively farmed were also relied on trading with those that fished. There were no national borders preventing the movement of people and the Jo Lupo traded the ngege fish with their Samia and Abagusii neighbours for grains, pots, cattle, and essential farming tools like iron hoes.[28] By 1900 the Luo had not developed the same level of specialism in agriculture as with fishing, however, and relied on farming knowledge from their Kipsigis and Kisii neighbours.[29]

Lake Victoria and water more generally featured heavily in the spirituality of the region’s Luo, Sukuma, and Basoga shore-folk. One respondent in Opondo’s study of the Luo explained that fishers would respect the water gods through established ritual: the leader of the fishing excursion would have to take a mouthful of water and spray it onto the canoe to honour the lake god before they departed, whilst the first of their fish had to be offered to the sea god when they returned.[30] For the Basoga, the Luganda language name for Lake Victoria is Nalubaale, a term that refers to their entire pantheon of gods, which they largely share with their Baganda neighbours.[31] For all of these tribes, rainmaking was an established aspect of agricultural practice. Lake Victoria was unique in that its water level was directly determined by precipitation; and in the view of the Luo, Sukuma, and Basoga, the rains in the sky were connected to the water in the ground. Whereas Westerners would view Lake Victoria as the pool of H2O that sits on the earth’s surface, in the local view the Nam Lolwe or Nalubaale refers to the “endless” or “divine” body of water that continuously circulates within what modern scientists would define as the LVB hydrological cycle. In Basoga cosmology, it is understood that their rain god Mesoké, who resides in Itanda Falls, carries the water from the river to the heavens in the form of a rainbow almost every morning.[32] The 3 million Basoga of Uganda who reside in the region around Jinja rely on rain-fed agriculture for subsistence. As is the case for all the rural agricultural communities discussed in this paper, receiving the right amount of rain at the right time was a matter of life or death. In the late 1890s, British explorer Henry Johnston observed that for the Basoga, who were plagued by drought, the rain god was the “most important personage among the gods.”[33] According to Johnston, the Basoga relied on bananas as their main crop, which often failed due to lack of rain thus resulting in famines among the community. He witnessed a rainmaking ritual in which a dance was followed by the mock sacrifice of a young girl, who was then thrown into the river as part of the performance (but quickly rescued).[34] Basoga deities are believed to reside in the water and its waterfalls, with the force of the waterfalls symbolizing the power of the spirits themselves. The Basoga gods and spirits are believed to intervene in human life; many are ill-tempered, and their wrath should be feared. The most powerful of these gods, namely Bujagali, Kiyira, and Itanda, have human spirit mediums who act as healers and messengers for the Basoga community.[35] For the deities to remain happy, they must be honoured through animal blood-sacrifices, although there are stories predating the twentieth century that describe mutilated children being thrown into the lake to appease the spirits.[36]

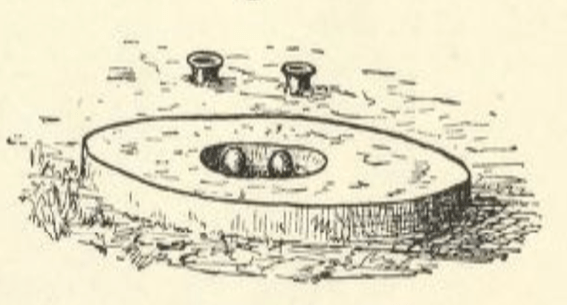

Whilst Johnston had commented on the drought experienced by the Basoga in the late 1890s, German lieutenant Karl Kollman remarked in 1899 that the “luxuriant pasture grounds” of Sukuma farmland in the Lake Victoria region of northern Tanzania were “so exceedingly fertile and productive that it might become the granary of other countries.”[37] The region near Mwanza Gulf was characterised by extensive ponds and pools which supplied the Sukuma farmers and herders with water throughout the drier seasons.[38] Kollman observed the importance of rainmaking among Sukuma medicine-men, noting that those who were unable to bring rains were ostracised whilst those who were successful were showered with gifts of up to 100 goats from the community, and he documented one of the common rainmaking apparatuses that they used (Figure 5).[39] To understand traditional Luo rain-making beliefs, which are not well-documented in this period, we can look at Grace Ogot’s short story “The Rain Came” in which a Luo girl called Oganda is sacrificed to the lake monster so that the rains will fall. Published in 1963, the text is a literary reconstruction of an old Luo foundation story which Ogot’s grandmother had recounted to her as a child. It is not a fictive piece or a myth, but an account rooted in Luo epistemic belief.[40] By reading traditional European travel accounts against the grain alongside the work of modern African scholars, therefore, we get a glimpse of what nineteenth century subsistence cultures looked like around the lake prior to British colonial rule.

Changes in fishing practices, c.1900-present

From the earliest days of their imperial presence in East Africa, British personnel recognised Lake Victoria’s potential to support vast and lucrative fisheries. The completion of the Mombasa to Kisumu railway in 1901 enabled fish to be transported from the lake to Nairobi’s marketplaces for the first time. Early twentieth century European fishing endeavours focused on the native cichlid species, but the nature of fishing changed when they introduced the first flax gill-net in 1905 followed by the beach seine.[41] Asian fishing traders introduced the first fishing dhows into the lake in the 1920s, whilst Europeans soon began to experiment with the use of trawlers.[42] European observers were quick to criticise local practices and raised concerns about overfishing in the lake. This stimulated the British colonial authorities to commission Martin Graham to conduct a survey of Lake Victoria’s fish population in 1927.[43] It is due to this economic interest in the region’s fishing industry that the biodiversity of fish species and ecological changes in Lake Victoria has been carefully documented by biologists and ecologists over the past 100 years.

Europeans viewed the local cichlid fish species with disdain, seeing them as “trash” and “vermin” because of their small size and relatively low commercial value on the international market.[44] This led to a series of debates about the introduction of non-native species into the lake.[45] It had been suggested that Nile perch (Lates niloticus), native to the Nile River region of Africa and the Middle East, would be commercially the best option for Lake Victoria as it was a “fine sporting and very edible fish”, yet Graham and other colonial scientists warned authorities about the ecological impact of introducing a new predator to the waters.[46] To prevent anybody from taking action until further research on the impacts of introducing a predatory fish like the Nile perch had been conducted, the East African High Commission passed the Lake Victoria Fisheries Act in 1950 which made it illegal for anybody to introduce non-native organisms into the water. A 1953 amendment then extended this to include all connecting rivers 1 mile upstream.[47] Only East African Fisheries Research Organization (EAFRO) and Lake Victoria Fisheries Services personnel were exempt from this rule. In reality, however, it was not practical or possible to police a 3,500km shoreline. It was not without criticism, moreover, that in 1953 EAFRO tried to combat the decline of tilapia in Lake Victoria by introducing four non-native tilapia species: Oreochromis leucostictus, Tilapia rendalli, Tilapia zillii, and Oreochromis niloticus. Of these, the latter, the Nile tilapia, is the best known. It is an omnivorous species that can tolerate poor water quality and it reaches sexual maturity very quickly, enabling fast population growth. Given its great durability, its introduction contributed to a decline in fish species diversity in Lake Victoria by approximately 50%.The Nile tilapia eventually supplanted the native tilapia species, although its ecological impact is considered minimal when compared to that of the Nile perch.[48]

After construction of the Owen Falls Dam took place in 1954, the Uganda Game and Fisheries Department (UGFD) gained sole jurisdiction over the upper Nile and Lake Kyoga and officer John Stoneman coordinated the deliberate movement of Nile perch in the region, most notably introducing 100 of the fish into Lake Kyoga. EAFRO agreed that they would wait to observe the results of the Lake Kyoga trial before deciding whether to introduce the Nile perch to Lake Victoria. Additionally, further biological research to improve understanding of the organism and its ecological function was commissioned to begin in 1959. By that time, however, the Nile perch had already been spotted in Lake Victoria’s waters, and it is unknown whether its illegal introduction in the mid-1950s was deliberate or accidental.[49] Robert M. Pringle concludes that it was most likely part of “repeated secretive introductions [that] were made in the mid-1950s by members of the Uganda Game and Fisheries Department as part of a bifurcated effort to improve sport fishing on the one hand and to bolster fisheries on the other.”[50] Once the Nile perch had invaded the lake, it gave British officers a convenient excuse to arrange to bring greater numbers of the fish into various locations around the north of Lake Victoria in the 1950s and 1960s to expand commercial opportunity and transform the fishing industry.[51]

There was a short delay before the impact of the Nile perch was felt within the region, but the 1980s witnessed an explosion in the Nile perch population that correlated with a fivefold increase in the economic value of the lake’s fishery.[52] In 1980, the Nile perch constituted less than 5% of catches among the fisheries of Lake Victoria, yet in 1989 it counted for over 60% (Figure 6).[53] The arrival of the new species led to a notable increase in fisher numbers as well as catch per unit in Tanzania, Kenya, and Uganda alike (Figure 7).[54] The fishing industry quickly attracted people from outside the traditional fisher-farmer tribes.[55] Only 5,000 fishers were recorded in the Kenyan part of Lake Victoria in 1929, yet this number had risen to 36,000 in 2001.[56] The relative importance of fishing within the national economies of Tanzania, Kenya, and Uganda also increased in accordance with this rapid growth of foreign exchange exports in Nile perch. Second to coffee, fish is Uganda’s second largest export today. The new species also created new markets for by-products such as kayobo, a sun-dried and salted form of Nile perch, which is an industry that employs many women on the Tanzanian shores of Lake Victoria.[57] By 2003, Kirumba Market in Mwanza had emerged as an international market for the Sukuma to sell this kind of dried fish, for example.[58] Fishing has become completely commercialised and the industry is dominated by large companies, with the average fish factory in LVB employing 100 people, 30% of whom are female.[59]To take an optimistic view, the Nile perch has increased the commercial value of every lake it has been introduced into; comparing statistics from the beginning and end of the twentieth century, fishery production in Lake Victoria has increased more than tenfold since it was introduced.[60]

Yet, the commercial benefits aside, the disruptive impact of the invasive Nile perch species on Lake Victoria’s ecosystem has been profound. The new species transformed what had been a diverse multi-species fishery into one that relies on only three primary species: the new Nile tilapia and Nile perch, and the native silver cyprinid (Rastrineobola Argentea).[61] The Nile perch became the sole dominant predator in the lake, disrupting a food chain that previously had over 100 species of predators. Its diet included the indigenous cichlid fish, and surveys revealed that the cichlid diminished from forming 80% of fish biomass in the lake in 1950 to constituting only 1% in 1980.[62] This has had negative impacts across the lake as cichlid play an important ecological role in the reduction of organic detritus, which sink to the lake floor and absorbs oxygen as it decays.[63] Scientific studies have linked the depletion of fish biomass by the Nile perch with the rise of phosphorous in the lake that caused rapid eutrophication in the 1980s.[64] Other biological studies have observed that eutrophication, in turn, has contributed to the decrease in cichlid species diversity in Lake Victoria. Reduction of light penetration in the water impacts the coloration of cichlid fish species causing dullness in colour, which consequently disrupts their sexual selection patterns based on colour signals. As a result, their mating takes place within a less diverse gene pool.[65] Given the profundity of these ecological changes, the Nile perch’s presence has had knock-on effects that extend throughout the entire food chain, with there being a decline in other fish species like catfish and lungfish and noted changes in the diets of kingfishers and otters.[66] As part of this food chain, the dietary habits of the Luo, Basoga, and Sukuma have been impacted too.

There is great poverty among Lake Victoria’s fishing communities today. Fishing among the Luo is now an activity associated with economic hardship.[67] In 1994, it was recorded that 50% of people living in Nyanza, Western, and Rift Valley provinces of Kenya lived in poverty. It is known as the “belt of poverty” where Kenya meets Lake Victoria’s shores.[68]The majority of fishers in Lake Victoria are small artisans or casual laborers who conduct their ventures close to the shores using canoes that are propelled by out-board motors. With the increase in catch size, there emerged a need for refrigeration and local fishers cannot afford larger boats with refrigeration facilities that are needed for fishing in deeper waters.[69] With the colonial state disregarding subsistence culture in favour of developing fishing for internal and external markets, fishing practices took a departure from the tradition of “free access” and have been regulated by licensing laws and subject to taxation since European arrival.[70] Many small fishers continue to operate without a license, however, trying their best to avoid the lake patrol police who demand bribes.[71] The closed season became legally enforced as did restrictions on net sizes.[72] Annual income fluctuated according with the ebbs and flows of international market prices, which were much less reliable than pre-colonial personal trading connections. Fishers now lose much of their profits to the middlemen and market agents who co-ordinate transactions. The continued domination of male fishers in the region and the gendered dimension of the role of middlemen today has been emphasised by Modesta Medard et al., who have studied the marginalisation of women within the Sukuma fishing industry in the twenty-first century where power is concentrated in the hands of a few male brokers.[73] Local fishers express their frustrations that the largest boats that appear on the water tend to be foreign-owned, and it is these outsiders who establish purely extractive relationships with the water and are responsible for overfishing. Commercialisation has also led to an increased demand for the most effective fishing gear, which is too expensive for the poorer fishermen to purchase.[74] In an effort to adapt to the new environmental pressures and economic competition, local fishing units have increased their hours on the lake and have spread further afield in search of productive fishing grounds. With the shift from cooperation to competition, it is also more common for fishers to sleep on their boats when they set nets, to avoid theft.[75] Surveys in the 1990s found that the shore-folk of Lake Victoria only ate fish once or twice a week. They still preferred to eat the smaller tilapia ngege fish, but they would sometimes consume juvenile Nile perch fish that had been rejected from the factories.[76] Despite their continued proximity to the lake, therefore, another major shift we can observe is that families in LVB no longer have access to fish as their major protein source. Moving away from traditional Eurocentric narratives about the lake’s “discovery”, therefore, European involvement with Lake Victoria and its shore-folk is perhaps better understood through a framework of disruption and encroachment.

Changes in rain-fed agricultural practices, c.1900-present

The damming of Lake Victoria was proposed by Henry Morton Stanley as early as 1878 and reiterated by other European explorers such as Winston Churchill.[77] Given the cultural and spiritual importance of waterfalls as homes of the Basoga gods, the Basoga came into conflict with the colonial state and postcolonial government in Uganda over the building of the Owen Falls Dam (now called the Nalubaale Dam) that was constructed 1949-1954, as well as the Bujagali Hydropower Dam completed in 2012 and the Isimba Dam built in 2017. Prior to colonial rule, there were no dams in Lake Victoria. Water levels were naturally regulated by a natural rock dam in the north side. When water levels were too high, the lake would spill over the rock into the White Nile. Owen Falls Dam, which was proposed by English engineer Sir Charles Redvers Westlake in 1947, was part of a larger British-commissioned urbanisation project in East Africa.[78]The hydroelectric dam was designed to solve Uganda’s energy problems, yet it was part of a broader colonial project of industrialisation around the region of Jinja. The British wanted to develop the region’s heavy industries in a way that was conceivably “modern”.[79]Belonging to this wider industrializing complex, the dam was built around the same time as a textile mill, for the processing of Ugandan lint cotton into exportable cotton, and a smelter at Jinja, for the processing of copper ore into exportable electrolytic copper.[80] In 1950 the Hereditary Abataka of Basoga wrote a letter of objection to the prime minister that read:

“The construction of the dam and the erection of the electric plant are not being done to benefit the Africa Basoga nor Uganda. But for the benefit of non-natives in Uganda. For we have no buildings in towns suiting the uses and the purposes for which the Dam and the electric power-plant are being carried out.”[81]

The colonial state’s lack of concern for the Basoga people is reflected in the fact that this letter was left unanswered. The EARC captured the popular view of the time when they said in 1955 that “East Africa needs the skill and capital of the non-African more than the non-African needs East Africa.”[82]

Dams posed a new kind of threat to Basoga spirituality. What was even more controversial than the fact that electricity would not benefit them, however, was that one of their female deities resided in Owen Falls.[83] Basoga cultural leaders came to heads over whether a spirit would be killed by a dam or if they could be relocated to a different waterfall. According to one source, a sacrifice of a goat took place near the Owen Falls in 1948 to appease the spirits before the dam was built, and it is believed by some that the female deity survives today.[84] Nevertheless, tensions reached their height when it was announced that the home of another spirit would be flooded during the construction of the Bujagali Hydropower Plant, which was inaugurated 8km north of Jinja in 2012.[85] The Basoga spirit medium Jaja Bujagali strongly opposed the building of the dam. According to Bujagali, the consequences of angering the gods included workers being injured during construction, breakdowns of machinery, disappearance of livestock, miscarriages and birth defects, foreign disease and pests, and mental breakdown.[86] The World Bank, the construction team, NGOs, and local communities all concurred that the Bujagali Falls was home to a number of ancestral and family spirits as well as Namamba Budhagaali, one of the Basoga’s most powerful spirits. There were 16 islands, 32 shrines, 10 large trees, 6 rocks, 20 burial grounds, 2 fireplaces and a culturally important forest in the immediate project area that was flooded.[87] This controversy delayed its construction for several years as the World Bank withheld its funding on the conditions that the dam project must minimise the social impacts of its construction to fit with international guidelines.[88] Construction of the dam had the support of some members of the Basoga, nonetheless, as well as President Museveni who described the controversy as “a circus”.[89] In an attempt to appease the Basoga protestors, the Ugandan government sponsored the ritual removal of the spirit from the rapids to a new location by a traditional healer called Nfuudu who used a bark spear to perform the ceremony on August 19, 2007. The government then created an “Agreement for the Mitigation of Cultural Impacts and Appeasement of the Budhagali Spirit,” which they claimed that the spirit Namamba Budhagaali signed himself. This performative ritual was opposed by the aforementioned Basoga cultural leader Bujagali, however, who labelled it as a charade and insisted that spirits cannot be moved from one place to another “like a goat.”[90] The gods are believed to remain angry about the Bujagali dam today, and their frustration resurfaced following the building of the Isimba dam in 2017, which coincided with a four-month period of drought. Although challenged by rapid urbanisation in the region that was set forth under the British colonial state in the 1940s, Mary Itanda, the spirit medium who lives among the Basoga community at Itanda Falls, responded to the drought through the age-old Basoga custom of rainmaking through animal sacrifice. In Mary Itanda’s view, however, the gods are becoming increasingly frustrated and withholding rains today as fewer and fewer Basoga people now worship them.

By the 1950s, rainmaking practices among Tanzania’s approximately 5 million Sukuma had virtually disappeared.[91] The reasons for its disappearance are multi-faceted and it cannot be dismissed within a “modernity versus tradition” binary in which it might be conceived as the triumph of Western epistemology, since the practice of witchcraft and witch-killings have increased as rainmaking declined.[92] Firstly, rainmaking faced increasing pressure from Europeans, Muslims, and Christians, especially the Catholic Missions. Secondly, Western education taught that the hydrological cycle was part of a scientific framework of meteorology. And, thirdly, radio transmission traversed the whole of Tanganyika by 1955, enabling people to listen to daily weather forecasts for the first time. None of these factors immediately dispelled Sukuma rainmaking beliefs, but they shifted the emphasis away from the traditional culture over time. The move away from rainmaking was cemented in 1963 when the first prime minister of Tanzania, Julius Nyerere, who had been educated in the UK under the British colonial system, abolished chiefdoms thus disabling the chiefs from fulfilling their rainmaking duties.[93] Some Sukuma elders interpreted the neglect for rainmaking practices as the cause of famine and declining fish species in Lake Victoria.[94] Changes in Sukuma agricultural practices occurred when the British introduced new crops to East Africa such as rice, cotton, and sugarcane.[95] It has been recorded that economic life marginally improved among the Sukuma in accordance with a boom in cotton farming in the mid-twentieth century. Agricultural production is still characterised by uncertainty in this drier part of the basin though, and most farmers have now shifted to cash crop cultivation.[96] Although rainmaking beliefs did not survive colonial penetration, water nevertheless remained an important aspect in Sukuma spirituality after independence, with their god Ngassa still being associated with water, and ritual washing and submergence into Lake Victoria being part of the initiation ceremonies of many of the spirit mediumship cults (Figure 8).

Flooding is a perennial problem on the Kenyan side of the basin. This is especially the case in the Luo village of Kanyibani in the Awach catchment of LVB, which is located between the rivers Awach and Sare and particularly prone to flooding due to its location at the foot of the Kericho and Nandi ridge fault lines. The smaller of the two rivers, the Sare, usually dries up during the months of January and February. During the rainy season, however, the Awach bursts its banks and floods the surrounding land. As already noted, flooding was factored into the Luo mode of life before 1900 as the rainy season coincided with the closed season in which the Luo let the lake “rest” and worked on their farmland further away from the shore.[97] Erosion after 1940 has made flooding in the area increasingly worse, however.[98] To manage flooding, the British administration introduced eucalyptus from Australia to drain swamps and wetlands.[99] They also oversaw the forced labor construction of soil terraces in Kanyibani village beginning in 1948. If villagers refused, their chiefs would oversee their imprisonment. Despite Bethwell Ogot noting that the Luo were very extremely cooperative with the European administration, this only seems to have been true regarding the chiefs in Kanyibani village.[100] European policies created anti-colonial feelings among ordinary laborers and stirred up resentment towards the flood defence structures themselves. When Kenya achieved independence in 1963, these flood defences were destroyed, and the Luo reverted to planting sorghum instead of eucalyptus. When researcher Mary Kerubo Nyasimi asked one of her oral interviewees what happened after the terraces were destroyed, they recalled that “unfortunately, Awach and Sare Rivers got angry and started pouring their water on our soil.”[101] In Kanyibani village today, the Luo have adapted their livelihoods in response to land degradation and increased flooding, and now engage in other occupations such as land lording and shop-keeping .[102]

Although their livelihoods are traditionally resilient, what we see is that the adaptive pressure of colonialism led to many Luo farmer-fishers becoming caught in a cycle of unreliable subsistence work and unstable employment. On top of flooding concerns, a study that used monthly and seasonal precipitation data for the period 1961-1999 in the Lake Victoria region of Kenya found that drought severity has also increased in more recent years.[103] Food insecurity (defined as the lack of enough food to provide energy for day-to-day activity) caused by drought and famine has devastating consequences given that many of the communities living near the lake are among the poorest in Kenya.[104] With the boom in fishing in the 1980s, some traditional fisher-farmer communities initially neglected their agricultural land.[105] As competition has intensified due to the ever-growing number of fishers on the lake and overfishing has led to a decline in fish species, however, Luo fishers increasingly turned towards agriculture to meet their household subsistence needs.[106] In the 1990s, fishers whose incomes were barely at subsistence level felt that the fishery was “increasingly unable to provide them with a higher income.”[107] Yet, simultaneous land pressures and the increased severity of floods and droughts coupled with low investment and the problem of plot fragmentation has pushed many Luo out of farming.[108] In the twenty-first century, most Luo were engaged in a “multiplex of non-farming activities” to supplement their incomes.[109] Mary Nyasimi et al. have observed “a total shift from farming to non-farming” among the Luo of Kanyibani Village.[110] Kim Geheb and Tony Binns describe this unavoidable “oscillation between farming and fishing” as a “vicious circle of over-exploitation and demise” in which the Luo are trapped. [111] In other words, both fishers and farmers have gone “part time” in an effort to adapt to the new, unreliable relationship with water that is their postcolonial reality. As a result of colonial intervention, fishing and farming now represent two parts of the Luo people’s multi-faceted survival strategy.

Conclusion

For East Africa’s freshwater shore-folk, the importance of Lake Victoria, its tributaries, and its life-giving rains could hardly be over-exaggerated. To quote the slogan of modern-day Jinja where the Basoga reside, “Kiyira [the river] gives richness.” [112] In the past 150 years, the relationships between the Luo, Sukuma, and Basoga and their traditional resource bases have been disrupted by European interventions. Although we know a lot about the ecological character of the lake given economic investment into its fishery by European scientists and colonial personnel since the early twentieth century and the fact its chronology has been preserved in Luo oral traditions which go back to at least the fifteenth century, there has been remarkably little scholarship discussing colonial management of the lake’s resources to date.[113] What I have attempted to do is to use a series of small case studies to weave together a narrative about how colonialism and postcolonialism in Tanzania, Kenya, and Uganda played out on the water. Through looking at the Luo of Kenya, Sukuma of Tanzania, and Basoga of Uganda, I have highlighted some of the impacts that the British “discovery” of Lake Victoria had on the local fishing communities and rain-fed agricultural societies that live on and around Lake Victoria’s shores. This is important because their needs and their cultural and natural heritage continue to be marginalised within development projects in the region today; the issues of poverty and famine that they are facing require urgent attention and, above all, international cooperation between the three riparian states.[114]

Taking a transnational approach, I have emphasised the arbitrariness of colonial borders when it comes to the study and management of an integrated water ecosystem. After the Nile perch were introduced to the Upper Nile and northern shores of the lake in Uganda in the 1950s and 1960s, the enormous fish which grew up to 200kg quickly spread throughout the region. They even destroyed the fishing nets of the Sukuma at the southern side of the lake in Mwanza Gulf, who began to speculate that there was a monster in the waters.[115] This anecdote might seem trivial, but what it highlights is that interventions that take place at one side of the lake impact people at the other side too. Located at the intersection of modern-day Tanzania, Kenya, and Uganda, Lake Victoria is in some ways a microcosm of East African regionalism. Joseph L. Awange has rightly observed that the people of LVB have a shared history built upon trading connection, cultural exchange, intermarriage and common experiences of external intervention such as the slave trade and colonialism.[116] To this, I would add that their experiences of subjugation under the British Empire were in many ways analogous, especially in terms of dealing with the interregional impacts and legacies of Britain’s resource management of the lake. Whereas Lake Victoria’s early African explorers practiced subsistence farming, British “discovery” led to irreversible environmental damage and profound changes in the region’s economy and society. British interventions in LVB destabilised the environmentally sustainable relationships that fishers and rain-reliant farmers had with Lake Victoria in the pre-colonial period, leading to greater job and food insecurity after independence and the decline in popularity (and in some cases the complete erasure) of cultural and spiritual traditions like rainmaking and the worship of water gods.

Bibliography

“Lake Victoria Basin Commission and the Lake Victoria Fisheries Organization.” International Waters Governance. www.internationalwatersgovernance.com/lake-victoria-basin-commission-and-the-lake-victoria-fisheries-organization.html.

“Lake Victoria Environmental Management Project – World Bank 1996-2002.” UN Water Activity Information System. www.ais.unwater.org/ais/aiscm/getprojectdoc.php?docid=3403.

Abila, Richard O. “Impacts of international fish trade: a case study of Lake Victoria fisheries” Responsible fish trade and food security. Fisheries technical paper no.456. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2007.

Awange et al., Joseph L. “Frequency and severity of drought in the Lake Victoria region (Kenya) and its effects on food security.” Climate Research 33 (2007), 135-142.

Awange, Joseph L. Lake Victoria Monitored from Space. Springer, 2021.

Awange, Joseph L. Lake Victoria: ecology, resources, environment. Netherlands: Springer, 2006.

Ballatore, Thomas. “Lake Victoria Basin: Population Density” and “Lake Victoria Basin: Annual Precipitation.” Lake Basin Action Network. 19 November 2012. http://www.lakebasin.org/maps/maps.html.

Byerley,A. Becoming Jinja. The Production of Space and Making of Place in and African Industrial Town. Stockholm: Stockholm University, 2005.

Carpenter, Frank G. Uganda to the Cape; Uganda, Zanzibar, Tanganyika Territory, Mozambique, Rhodesia, Union of South Africa. Garden City N.Y.: Doubleday, Page & Company, 1924.

Chapman, L. J., et al.“Fish faunal resurgence in Lake Nabugabo, East Africa.” Conservation Biology 17 (2003), 500-511.

Cory, Hans. Traditional Rites in Connection with the Burial, Election, Enthronement and Magic Powers of a Sukuma Chief. London: Macmillan and Co. Ltd, 1951.

Deisser, Anne-Marie and Mugwima Njuguna, editors. Conservation of Natural and Cultural Heritage in Kenya. London: UCL Press, 2016.

EAFRO. “The history and research results of the East African Freshwater Fisheries Research Organization from 1946 – 1966.” Aqua Docs. http://hdl.handle.net/1834/32645.

Gehab, Kim and Tony Binns. “‘Fishing farmers’ or ‘farming fishermen’? The quest for household income and nutritional security on the Kenyan shores of Lake Victoria.” African Affairs 96 (1997), 73-93.

Goldschmidt, Tijs. Darwin’s Dreampond: Drama in Lake Victoria. Translated by Sherry Marx-Macdonald. Massachusetts and London: the MIT Press, 1996.

Graham, Martin. The Victoria Nyanza and Its Fisheries: A Report on the Fish Survey of Lake Victoria 1927–1928 and Appendices. London: Crown Agents for the Colonies, 1929.

Heale, Jay and Winnie Wong. Tanzania. China: Marshall Cavendish, 2010.

Johnston, Henry. The Uganda Protectorate. Volume 2. London: Hutchinson & Co., 1904.

Kenny, Michael G. “The Powers of Lake Victoria.” Anthropos 72.5-6 (1997), 717-733.

Kollman, Paul. The Victoria Nyanza; the land, the races and their customs, with specimens of some of the dialects. London: S. Sonnenschein & Co., ltd, 1899.

Komey, Ellis and Ezekiel Mphahlele, editors. Modern African Stories. London: Faber and Faber, 1964.

Kurien, J. editor. Responsible fish trade and food security. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2005.

Lehman, John T., editor. Environmental Changes and response in East African Lakes. Springer: 1988.

Lindfors, Bernth. “Interview with Grace Ogot.” The Journal of Postcolonial Writing 18.1 (1979), 57-68.

Medard, Modesta et al. “Competing for kayabo: gendered struggles for fish and livelihood on the shore of Lake Victoria.” Maritime Studies 18 (2019), 321-333.

NASA Earth Observatory. “Drought and Dams.” March 2006. earthobservatory.nasa.gov/features/Victoria/victoria2.php.

Nyasimi, Mary Kerubo. “Changing capitals, shifting livelihoods: case study of Luo community living on Awach catchment of Lake Victoria Basin, Western Kenya.” Master’s Thesis, Iowa State University, 2006.

Nyasimi, Mary, et al. “Differentiating livelihood strategies among the Luo and Kipsigis people in Western Kenya.” Journal of ecological anthropology 11.1 (2007), 43-57.

Oestigaard, Terge. Damned Divinities: The Water Powers at Bujagali Falls, Uganda. Uppsala: Nordiska Afrikainstitutet, 2015.

Oestigaard, Terge. Rainbows, pythons and waterfalls: heritage, poverty and sacrifice among the Busoga in Uganda. Uppsala: Nordic Africa Institute, 2019.

Oestigaard, Terge. Religion at Work in Globalised Traditions: Rainmaking, Witchcraft and Christianity in Tanzania. Newcastle Upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2014.

Ogot, Bethwell. “British Administration in the Central Nyanza District of Kenya, 1900-60.” The Journal of African History 4.2 (1963), 249-273.

Ogot, Bethwell. Peoples of East Africa: History of the Southern Luo. Volume 1: Migration and Settlement 1500-1900. Nairobi: East African Publishing House, 1967.

Pitcher, T.J. and P. J. B. Hart, editors. The Impact of Species Changes in African Lakes. London: Chapman and Hall, 1985.

Pringle, Robert M. “The Origins of the Nile Perch in Lake Victoria.” Biology in History 55.9 (2005), 780-787.

Sanders, Todd. Beyond Bodies: Rainmaking and Sense Making in Tanzania. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2008.

Seehausen, Ole et al. “Cichlid fish diversity threatened by eutrophication that curbs sexual selection.” Science 227.5333 (1997), 1808-1811.

Speke, John Hanning. Journal of the discovery of the source of the Nile. New York: Harper, 1863.

Speke, John Hanning. What led to the discovery of the source of the Nile. Edinburgh: William Blackwood and Sons, 1864.

Taabu-Munyaho, A., et al. “Nile perch and the transformation of Lake Victoria.” African Journal of Aquatic Science 41.2 (2016), 127.

The International Water Association et al. “Flood Drought and Management Tools: Lake Victoria Basin.” https://fdmt.iwlearn.org/.

US Department of State Archive, “Invasive Species: Case Study: Tilapia.” 2001-2009. https://2001-2009.state.gov/g/oes/ocns/inv/cs/2310.htm.

Witte, Frans et al. “The Fish Fauna of Lake Victoria during a Century of Human Induced Perturbations,” Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on African Fish and Fisheries (2013), 49-66.

[1] Nyanza is a Bantu-language word meaning “lake”, and just one of the many local names for this body of water. John Hanning Speke, Journal of the discovery of the source of the Nile (New York: Harper, 1863); John Hanning Speke, What led to the discovery of the source of the Nile (Edinburgh: William Blackwood and Sons, 1864).

[2] One popular American-authored travel account from 1924, for example, stated “No one knew that Lake Victoria existed until Speke discovered the southern shores in 1858.” Frank G. Carpenter, Uganda to the Cape; Uganda, Zanzibar, Tanganyika Territory, Mozambique, Rhodesia, Union of South Africa (Garden City N.Y.: Doubleday, Page & Company, 1924), 6.

[3] Joseph L. Awange, Lake Victoria: ecology, resources, environment (Netherlands: Springer, 2006), 14; Joseph L. Awange, Lake Victoria Monitored from Space (Springer, 2021), 34.

[4] Smaller tribes around the basin include the Nazaki, Jita, and Kerewe of Tanzania, the Banyala and Suba of Kenya, and the Samia of Uganda. The region has also attracted small numbers of South Asian migrants. Awange, Lake Victoria: ecology, resources, environment, 14.

[5] Although it might seem that Kenyans are only exposed to a small portion of the lake, the lake has a long and weaving shoreline that creates many bays and inlets, including environmentally and economically important swamps and wetlands. Surface area per territory is by no means an indicator of a country’s relative reliance on Lake Victoria, as 17% of the shoreline falls within the territory of Kenya, whereas only 33% falls within Tanzania. NASA Earth Observatory, “Drought and Dams”, March 2006, earthobservatory.nasa.gov/features/Victoria/victoria2.php; Awange, Lake Victoria: ecology, resources, environment, 8.

[6] Awange, Lake Victoria: ecology, resources, environment, 32.

[7] Mary Kerubo Nyasimi, “Changing capitals, shifting livelihoods: case study of Luo community living on Awach catchment of Lake Victoria Basin, Western Kenya”, Master’s Thesis, Iowa State University, 2006, 2.

[8] 44% of the drainage basin is in Tanzania, 22% in Kenya, 16% in Uganda, 11% in Rwanda, and 7% in Burundi. The International Water Association et al. “Flood Drought and Management Tools: Lake Victoria Basin,” https://fdmt.iwlearn.org/, 1.

[9] The Caspian Sea is sometimes listed as the world’s largest lake, although it is not freshwater. The largest freshwater body of inland water is Lake Superior in the United States. The International Water Association et al.,“Flood Drought and Management Tools: Lake Victoria Basin,” https://fdmt.iwlearn.org/, 1.

[10] Its maximum depth is approximately 80m, meaning that it has a much lower volume of water than other large lakes in Africa. For example, its volume is only 15% of the volume of Lake Tanganyika, which ranks as the fifth largest freshwater lake in the world. In terms of its water temperature, Lake Victoria experiences very little annual variation. At the surface, the mean water temperature is 24oC and this decreases to 23oC at deeper parts of the lake. Awange, Lake Victoria: ecology, resources, environment, 7-8.

[11] Tijs Goldschmidt, Darwin’s Dreampond: Drama in Lake Victoria, translated by Sherry Marx-Macdonald (Massachusetts and London: the MIT Press, 1996), 5-8; Awange, Lake Victoria: ecology, resources, environment, 1, 8; Awange, Lake Victoria Monitored from Space, 34.

[12] Nicholson, Sharon E. “Historical Fluctuations of Lake Victoria and other lakes in the Northern Rift Valley of East Africa”, in Environmental Changes and response in East African Lakes, edited by John T. Lehman (Springer: 1988), 9-10.

[13] Joseph L. Awange et al., “Frequency and severity of drought in the Lake Victoria region (Kenya) and its effects on food security,” Climate Research 33 (2007), 136;Awange, Lake Victoria: ecology, resources, environment, 8.

[14] Lehman, ed., Environmental Changes and response in East African Lakes, 19.

[15] William Ochieng’ cited in Paul Opondo, “Fisheries as heritage: indigenous methods of fishing and conservation among the Luo fishers of Lake Victoria, Kenya,” in Conservation of Natural and Cultural Heritage in Kenya, edited by Anne-Marie Deisser and Mugwima Njuguna (London: UCL Press, 2016), 203.

[16] Opondo, “Fisheries as heritage,” 206; Martin Graham, The Victoria Nyanza and Its Fisheries: A Report on the Fish Survey of Lake Victoria 1927–1928 and Appendices (London: Crown Agents for the Colonies, 1929).

[17] Opondo, “Fisheries as heritage,” 204, 207-208.

[18] Opondo, “Fisheries as heritage,” 207.

[19] Opondo, “Fisheries as heritage,” 204.

[20] Paul Kollman, The Victoria Nyanza; the land, the races and their customs, with specimens of some of the dialects (London: S. Sonnenschein & Co., ltd, 1899), 148; Awange, Lake Victoria: ecology, resources, environment, 9.

[21] Opondo, “Fisheries as heritage,” 205-208.

[22] Bethwell Ogot, Peoples of East Africa: History of the Southern Luo. Volume 1: Migration and Settlement 1500-1900 (Nairobi: East African Publishing House, 1967), 37, 41.

[23] Bethwell Ogot, “British Administration in the Central Nyanza District of Kenya, 1900-60,” The Journal of African History 4.2 (1963), 252.

[24] Fishers did not just supply their own families but gave fish to more deprived members of the community, such as orphans. Opondo, “Fisheries as heritage,” 208.

[25] Jay Heale and Winnie Wong, Tanzania (China: Marshall Cavendish, 2010), 9.

[26] It was also a taboo among the Luo to eat lemons or bathe in soap before a fishing trip, as these were considered water pollutants. Fishers who disobeyed the elders and fished during the closed season could face punishment of being banned from the lake for several months. Opondo, “Fisheries as heritage,” 201, 204, 206.

[27] Opondo, “Fisheries as heritage,” 209; Nyasimi, “Changing capitals, shifting livelihoods: case study of Luo community living on Awach catchment of Lake Victoria Basin, Western Kenya”, 89.

[28] Opondo, “Fisheries as heritage,” 205.

[29] Nyasimi, “Changing capitals, shifting livelihoods: case study of Luo community living on Awach catchment of Lake Victoria Basin, Western Kenya,” 89.

[30] Opondo, “Fisheries as heritage,” 206.

[31] In the mid-1960s John Roscoe noted that the Baganda, who shared many cultural practices and religious beliefs with their tribal neighbors, believed that their deity Makasa (who is also worshipped by the monotheistic Sukuma under the name Ngassa) was a guardian of Lake Victoria, and in some sense embodied the lake itself. Michael G. Kenny, “The Powers of Lake Victoria,” Anthropos 72.5-6 (1997), 720.

[32] Terge Oestigaard, Rainbows, pythons and waterfalls: heritage, poverty and sacrifice among the Busoga in Uganda (Uppsala: Nordic Africa Institute, 2019), 68-69.

[33] Henry Johnston, The Uganda Protectorate, Volume 2(London: Hutchinson & Co., 1904), 719.

[34] Johnston, The Uganda Protectorate, 720.

[35] Some of these spirits also take the form of the python, lion, or leopard and move around. Oestigaard, Rainbows, pythons and waterfalls, 67.

[36] Johnston, The Uganda Protectorate, 719-720.

[37] Kollman, The Victoria Nyanza, 138.

[38] Kollman, The Victoria Nyanza, 138; Todd Sanders, Beyond Bodies: Rainmaking and Sense Making in Tanzania (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2008), 33.

[39] A fuller description of the use of this apparatus is recorded by Cory Hans in 1951. Cory Hans, Traditional Rites in Connection with the Burial, Election, Enthronement and Magic Powers of a Sukuma Chief (London: Macmillan and Co. Ltd, 1951); Kollman, The Victoria Nyanza, 168.

[40] Grace Ogot, “The Rain Came,” in Modern African Stories, edited by Ellis Komey and Ezekiel Mphahlele (London: Faber and Faber, 1964), 180-189; Bernth Lindfors, “Interview with Grace Ogot,” The Journal of Postcolonial Writing 18.1 (1979), 57-68.

[41] Goldschmidt, Darwin’s Dreampond, 229; Graham, The Victoria Nyanza and Its Fisheries; Robert M. Pringle, “The Origins of the Nile Perch in Lake Victoria,” Biology in History 55.9 (2005), 781; Kim Gehab and Tony Binns, “‘Fishing farmers’ or ‘farming fishermen’? The quest for household income and nutritional security on the Kenyan shores of Lake Victoria,” African Affairs 96 (1997), 78.

[42] Richard O. Abila, “Impacts of international fish trade: a case study of Lake Victoria fisheries,” Responsible fish trade and food security. Fisheries technical paper no.456, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2007.

[43] Pringle, “The Origins of the Nile Perch in Lake Victoria,” 781.

[44] Pringle, “The Origins of the Nile Perch in Lake Victoria,” 783.

[45] This practice was not new in the British colonies, with trout having been introduced to many of Kenya’s rivers to entice settlers to the region in the 1890s for example. Pringle, “The Origins of the Nile Perch in Lake Victoria,” 782.

[46] Bruce Kinloch, 1952, cited in Pringle, “The Origins of the Nile Perch in Lake Victoria,” 783; E. J. H. Oorloff, Letter to Nyanza senior commissioner, 5 September 1921, Nairobi Kenya National Archive File KP/4/7/1, cited in Pringle, “The Origins of the Nile Perch in Lake Victoria,” 781.

[47] Pringle, “The Origins of the Nile Perch in Lake Victoria,” 781; US Department of State Archive, “Invasive Species: Case Study: Tilapia”, 2001-2009, https://2001-2009.state.gov/g/oes/ocns/inv/cs/2310.htm; L. J. Chapman, et al., “Fish faunal resurgence in Lake Nabugabo, East Africa,” Conservation Biology 17 (2003), 500-511; Goldschmidt, Darwin’s Dreampond, 229.

[48] The management of fishing activity in the lake was further complicated by the different administrative structures in Uganda, where fisheries were the responsibility of the Game Department; in Kenya, where it was managed by Agriculture; and in Tanganyika, where it fell within the duties of Administration. Pringle, “The Origins of the Nile Perch in Lake Victoria,” 781.

[49] EAFRO, Annual Report, Kampala (Uganda): Uganda Argus [EAHC], cited in Pringle, “The Origins of the Nile Perch in Lake Victoria,” 783.

[50] Pringle, “The Origins of the Nile Perch in Lake Victoria,” 780.

[51] New Nile perch populations were introduced at Murchiston Falls in 1954; Masindi Port and the upper Nile below the Owen Fall dam in 1955; Port Bell in 1954/5; Entebbe Pier in 1962-63; Kisumu, Lake Nabugabo, Lake Saka, and Lake Kijanebalola in 1963; and the Kagera River on an unknown date. The furthest point of advance of the fish was recorded at the lake’s southern reach in Mwanza, Tanganyika in 1961. Pringle, “The Origins of the Nile Perch in Lake Victoria,” 784.

[52] J. E. Reynolds, et al., “Thirty years on: The development of the Nile perch fishery in Lake Victoria,” in The Impact of Species Changes in African Lakes, edited by T.J. Pitcher and P. J. B. Hart (London: Chapman and Hall, 1985), 181-214.

[53] Reynolds, et al., “Thirty years on: The development of the Nile perch fishery in Lake Victoria,” 185.

[54] Reynolds, et al., “Thirty years on: The development of the Nile perch fishery in Lake Victoria,” 189.

[55] Gehab and Binns, “‘Fishing farmers’ or ‘farming fishermen’?,” 83.

[56] Awange, Lake Victoria: ecology, resources, environment, 32.

[57] Modesta Medard, et al. “Competing for kayabo: gendered struggles for fish and livelihood on the shore of Lake Victoria,” Maritime Studies 18 (2019), 322.

[58] Medard, et al. “Competing for kayabo: gendered struggles for fish and livelihood on the shore of Lake Victoria,” 326.

[59] Abila, “Impacts of international fish trade: a case study of Lake Victoria fisheries,” 35.

[60] A. Taabu-Munyaho, et al. “Nile perch and the transformation of Lake Victoria,” African Journal of Aquatic Science 41.2 (2016), 127.

[61] The silver cyprinid increased in numbers following the introduction of the Nile perch, although the precise reasons for this is not known. It is also called the Lake Victoria sardine, known locally as omena in Kenya; mukene in Uganda; nsalali in Tanzania; and dagaa among the Sukumu of Tanzania. Frans Witte, et al. “The Fish Fauna of Lake Victoria during a Century of Human Induced Perturbations,” Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on African Fish and Fisheries (2013), 49-66.

[62] Goldschmidt, Darwin’s Dreampond, 229.

[63] Graham, The Victoria Nyanza and Its Fisheries; US Department of State Archive, “Invasive Species: Case Study: Tilapia”; Goldschmidt, Darwin’s Dreampond, 229.

[64] In more recent years, eutrophication has worsened due to the invasive water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes) coupled with increasing water pollution and atmospheric pollution. Awange, Lake Victoria: ecology, resources, environment, 125; Taabu-Munyaho, et al. “Nile perch and the transformation of Lake Victoria”, 127.

[65] As recognised in a study of the Halochromis genus in the Mwzana Gulf by Tijs Golschmidt, Lake Victoria was home to a unique species flock, meaning that there were various cichlid species within a defined area that are likely to have derived from a common ancestor. Although cichlid in the north had been studied by in the 1950s by Humphry Greenwood, former curator of London’s Museum of Natural History, it was not until the 1970s that the fish in the Tanzanian parts of the water came to be known when 150 new species were charted by the Haplochromis Ecology Survey Team. According to Golschmidt, the enormous diversity among the Haplochromis genusand their exemplified capability for such rapid genetic changes constitutes an evolutionary case study far more impressive and intricate than Darwin’s finches of the Galápagos Islands. Lake Victoria, which Golschmidt terms “Darwin’s Dreampond”, therefore has a lot to offer the advancement of human understanding of evolutionary biology and natural selection. Ole Seehausen, et al., “Cichlid fish diversity threatened by eutrophication that curbs sexual selection,” Science 227.5333 (1997), 1808-1811; Goldschmidt, Darwin’s Dreampond, 5-8.

[66] Goldschmidt, Darwin’s Dreampond, 229-230.

[67] Nyasimi, “Changing capitals, shifting livelihoods: case study of Luo community living on Awach catchment of Lake Victoria Basin, Western Kenya”, 100-101.

[68] Awange, Lake Victoria: ecology, resources, environment, 191, 239.

[69] Awange, Lake Victoria: ecology, resources, environment, 26.

[70] Opondo, “Fisheries as heritage,” 201.

[71] Mary Nyasimi, et al. “Differentiating livelihood strategies among the Luo and Kipsigis people in Western Kenya,” Journal of ecological anthropology 11.1 (2007), 50.

[72] Gehab and Binns, “‘Fishing farmers’ or ‘farming fishermen’?,” 79.

[73] Medard, et al. “Competing for kayabo: gendered struggles for fish and livelihood on the shore of Lake Victoria,” 322.

[74] Awange, Lake Victoria: ecology, resources, environment, 26; Modesta Medard, et al. “Competing for kayabo: gendered struggles for fish and livelihood on the shore of Lake Victoria,” Maritime Studies 18 (2019), 324; Abila, “Impacts of international fish trade: a case study of Lake Victoria fisheries,” 52.

[75] Gehab and Binns, “‘Fishing farmers’ or ‘farming fishermen’?,” 86.

[76]Abila, “Impacts of international fish trade: a case study of Lake Victoria fisheries,” 39-41.

[77] Terge Oestigaard, Damned Divinities: The Water Powers at Bujagali Falls, Uganda (Uppsala: Nordiska Afrikainstitutet, 2015), 17.

[78] Following Westlake’s suggestion, the Uganda Electricity Board (UEB) was founded, and Westlake was appointed as its first chairman. The UEB proceeded to strike an agreement with Egypt in line with the 1929 Anglo-Egyptian treaty, agreeing that there would be no impacts on the natural flow of the Nile.

[79] A. Byerley, Becoming Jinja. The Production of Space and Making of Place in and African Industrial Town. (Stockholm: Stockholm University, 2005), 248-249.

[80] Byerley, Becoming Jinja. The Production of Space and Making of Place in and African Industrial Town, 249-250.

[81] Letter from Office of the Hereditary Abataka of Busoga to the Prime Minister, Mr. C. Atlee, 20 June 1950, CO536/221/5, cited in Byerley, Becoming Jinja. The Production of Space and Making of Place in and African Industrial Town, 264.

[82] EARC, 1955, cited in Byerley, Becoming Jinja. The Production of Space and Making of Place in and African Industrial Town, 265.

[83] Oestigaard, Damned Divinities: The Water Powers at Bujagali Falls, Uganda, 25.

[84] Oestigaard, Damned Divinities: The Water Powers at Bujagali Falls, Uganda, 25.

[85] Oestigaard, Damned Divinities: The Water Powers at Bujagali Falls, Uganda, 7.

[86] Oestigaard, Damned Divinities: The Water Powers at Bujagali Falls, Uganda, 51.

[87] About 634 people (85 households) had to be relocated to allow for the first stage of its construction. A further 900 people were disrupted and needed to be recompensated during the construction of the transmission lines, and approximately 5,158 individuals were impacted in total, which is relatively a small impact in terms of dam construction. Oestigaard, Damned Divinities: The Water Powers at Bujagali Falls, Uganda, 29, 49.

[88] Oestigaard, Damned Divinities: The Water Powers at Bujagali Falls, Uganda, 20.

[89] Oestigaard, Damned Divinities: The Water Powers at Bujagali Falls, Uganda, 49-50, 144.

[90] Oestigaard, Damned Divinities: The Water Powers at Bujagali Falls, Uganda, 21.

[91] Terge Oestigaard, Religion at Work in Globalised Traditions: Rainmaking, Witchcraft and Christianity in Tanzania (Newcastle Upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2014), 25.

[92] Oestigaard, Religion at Work in Globalised Traditions, 43.

[93] Oestigaard, Religion at Work in Globalised Traditions, 26.

[94] Oestigaard, Religion at Work in Globalised Traditions, 136.

[95] Nyasimi, “Changing capitals, shifting livelihoods: case study of Luo community living on Awach catchment of Lake Victoria Basin, Western Kenya,” 84.

[96] R. E. S. Tanner, “The Theory and Practice of Sukuma Spirit Mediumship,” in Spirit Mediumship and Society in Africa, edited by John Beattie and John Middleton (London: Routledge, 1969), 273.

[97] Opondo, “Fisheries as heritage,” 206.

[98] Mary Kerubo Nyasimi, “Changing capitals, shifting livelihoods: case study of Luo community living on Awach catchment of Lake Victoria Basin, Western Kenya,” 36, 84.

[99] Nyasimi, “Changing capitals, shifting livelihoods: case study of Luo community living on Awach catchment of Lake Victoria Basin, Western Kenya,” 84.

[100] Ogot, “British Administration in the Central Nyanza District of Kenya, 1900-60,” 249.

[101] Nyasimi, “Changing capitals, shifting livelihoods: case study of Luo community living on Awach catchment of Lake Victoria Basin, Western Kenya,” 84.

[102] Nyasimi, “Changing capitals, shifting livelihoods: case study of Luo community living on Awach catchment of Lake Victoria Basin, Western Kenya,” xiv.

[103] Awange et al., “Frequency and severity of drought in the Lake Victoria region (Kenya) and its effects on food security,”137.

[104] Awange et al., “Frequency and severity of drought in the Lake Victoria region (Kenya) and its effects on food security,”137.

[105] Gehab and Binns, “‘Fishing farmers’ or ‘farming fishermen’?,” 90.

[106] Gehab and Binns, “‘Fishing farmers’ or ‘farming fishermen’?,” 73.

[107] Gehab and Binns, “‘Fishing farmers’ or ‘farming fishermen’?,” 86.

[108] Gehab and Binns, “‘Fishing farmers’ or ‘farming fishermen’? The quest for household income and nutritional security on the Kenyan shores of Lake Victoria,” 73.

[109] Nyasimi, et al. “Differentiating livelihood strategies among the Luo and Kipsigis people in Western Kenya,” 55.

[110] Nyasimi, et al. “Differentiating livelihood strategies among the Luo and Kipsigis people in Western Kenya,” 53.

[111] Gehab and Binns, “‘Fishing farmers’ or ‘farming fishermen’?,” 76, 92.

[112] Oestigaard, Damned Divinities: The Water Powers at Bujagali Falls, Uganda, 18.

[113] Nicholson, “Historical Fluctuations of Lake Victoria and other lakes in the Northern Rift Valley of East Africa,” 7.

[114] These cooperate efforts are now formalised under the East African Community (EAC) treaty of 1999 signed by Tanzania, Kenya, Uganda, Rwanda, and Burundi, although have manifested through the channels of various organizations and projects funded by the World Bank and other international partners. International management efforts have been numerous since British rule, but include: establishment of the East African Freshwater Fisheries Research Organization (EAFRO) and Lake Victoria Fisheries Board in 1947; the establishment of The Lake Victoria Basin Commission (LVDC), a specialised institution under the EAC developed from their Lake Victoria Development Programme launched in 2001; the Lake Victoria Fisheries Management Organization, another specialised institution of the EAC formed in 1994; the Lake Victoria Environment Management Project (LVEMP) of 1994, signed by Tanzania, Kenya, Uganda, and the World Bank; The 2001 Partnership Agreement on the Promotion of Sustainable Development in Lake Victoria between the EAC and governments of Sweden, France, Norway, the World Bank, and the East African Development Bank; the Lake Victoria Management Project funded by the World Bank 1996-2002; and The Nile River Basin Initiative (NBI) signed by the EAC and NBI in 2006. “Lake Victoria Basin Commission and the Lake Victoria Fisheries Organization,” International Waters Governance, www.internationalwatersgovernance.com/lake-victoria-basin-commission-and-the-lake-victoria-fisheries-organization.html, accessed 1 May 2023; EAFRO, “The history and research results of the East African Freshwater Fisheries Research Organization from 1946 – 1966.”, Aqua Docs, http://hdl.handle.net/1834/32645, accessed 1 May 2023; “Lake Victoria Environmental Management Project – World Bank 1996-2002,” UN Water Activity Information System, www.ais.unwater.org/ais/aiscm/getprojectdoc.php?docid=3403.

[115] Goldschmidt, Darwin’s Dreampond, 10.

[116] Awange, Lake Victoria: ecology, resources, environment, 15.